Someone in my boardgame Discord posted a link to an episode from This Jungian Life, a podcast by three American analysts who take a look at cultural and interpersonal issues through a Jungian lens. The episode is entitled GAMES: metaphor for life, and the OP said most of it contained pretty obvious observations about games–in the midst of which was a statement that games were a sociopathic activity because they allow us to be indifferent to our opponents’ loss or suffering as long as it’s within the bounds of rules.

So obviously I had to check this out for myself. Were these Jungians really dumping on boardgames?

Me and Jung go pretty far back, actually. I was first introduced to his ideas back in high school English in the novel Fifth Business by Robertson Davies. I liked the book so much I read the rest of the trilogy it belonged to. A few years later I found myself working at Toronto’s only bookstore that specialized in psychiatry, psychology, and psychoanalysis (Caversham Booksellers), so I got to do a lot of free reading there as long as I didn’t get the books dirty. (I once had to pay for a copy of one of Camille Paglia’s books because I got hot and sour soup on it.)

What I liked about Jung’s philosophy is that it felt universal, in that it made connections between cultures both past and present to identify those tropes–he called them archetypes–that all human cultures share. Later I discovered Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces which expanded on these universal narratives.

So as I listened to the podcast episode, I heard far more nuance than just “games are for sociopaths”. Yes, the hosts do riff on how “gaming” is synonymous with trickery, betting on others’ suffering, exploiting others in order to satisfy the need for dominance, and allow us to distance ourselves from others by treating life “like a game”–as an abstraction–and so on. They discuss Greek mythology and the Book of Job as classic cases of The Gods meddling in human affairs for their own “gaming” purposes, quoting Gloucester from King Lear: “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; They kill us for their sport.”

There’s also some talk of society, culture, and economic systems as games. Game theory, an intersection of mathematics and economic theory, is brought up, with a basic explanation of The Prisoner’s Dilemma which left out the important point that the optimal solution to this problem depends on whether you are dealing with a one-off situation (which indeed favours “defection”) or repeated interactions (which has been shown both theoretically and empirically to be dominated by cooperative strategies). I can’t fault the Jungians for not knowing this–it’s outside their specialty–but it’s an important point.

So while a fair bit of the episode is about the “shadow” elements of games and gaming, right near the beginning of the episode someone makes the comment that games have an important role in nurturing resilience and connection because of how they contain people’s frustration–you learn that you might lose a game, but your friendship continues. Games provide an area of safety to work out feelings of aggression, they provide us with the ability to deal with the vagaries of Fate.

All of these observations are based on a broad definition of “games” that extends far beyond the tabletop world. The podcasters also make a distinction between games played by children versus those played by adults, which is clearly based on their own experience with games in their lifetimes–all the podcasters appear to be in their forties at least.

These memories are dominated by childhood plays of Monopoly, although one mentioned playing Pandemic with their family. The only other games that get significant mention are Chess and Poker–the latter specifically being used as an emblematic example of an “adult” game. Dungeons & Dragons gets one mention near the start of the episode, the only role-playing game to be mentioned.

There are also some insights near the end of the episode which added something profound to my understanding of the role games play in our lives. First was the statement that something inside us uses games to help us prepare for life by allowing us to use them to experiment with different strategies in an abstract, safe, and consequence-free environment before the real-life consequences of those strategies become excessive. Dreams may then be a kind of “immersive game” in which our unconscious tries to put us into certain problematic situations so that we can “game them out” to evolve real-life strategies in order to deal with them. I really like those ideas.

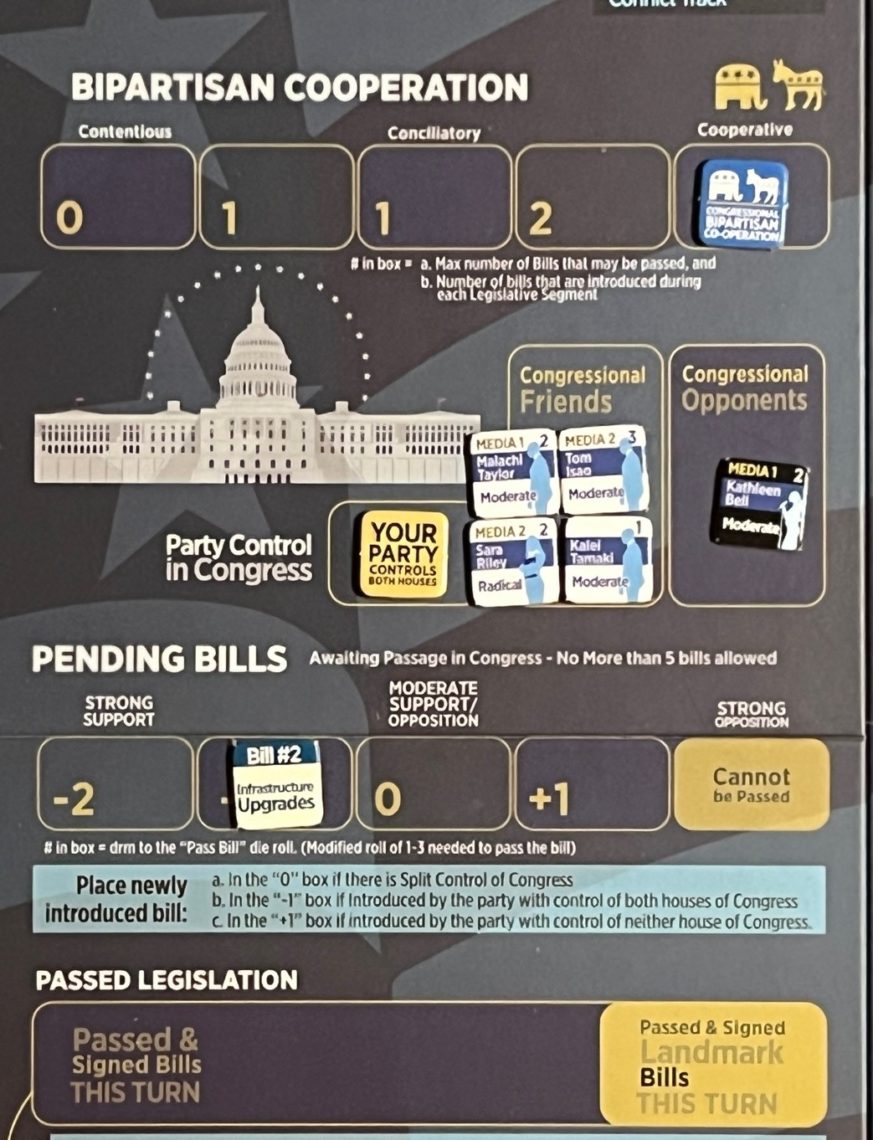

All of this being to the good, however, I cannot help but feel This Jungian Life’s analysis of games and their function neither includes or reflects the state of the art of tabletop gaming today, and I believe this results in an incomplete and surface-level take on Jungian elements in games. Their take of “games as preparation for life” presented in the podcast would probably be unprepared for modern works like Rise Up!, Bloc by Bloc, and Mapmaker: The Gerrymandering Game belong, which not only educate about real-world issues but serve as intentional rallying points to take real-world action.

The rest of this article is my (admittedly amateurish) attempt to fill in these gaps to illustrate how modern tabletop games embody Jungian principles to a far deeper extent than the hosts of This Jungian Life realize.

At the heart of this basic misapprehension is their belief that games’ primary (if not sole) function relates to fulfilling purely competitive drives in humans, in which there can only be zero-sum kinds of outcomes. Although, as I previously stated, Pandemic was mentioned in passing, the hosts probably don’t realize the extent to which co-operative games have become so popular in modern Tabletop. Nor do they probably know how many role-playing games there are which move far beyond Tolkienesque fantasy.

As I outlined in my discussion two years ago, games fulfill at least fifteen distinct intrapersonal and interpersonal needs–of which the need to dominate and the need to challenge oneself (the ones mentioned most often in the episode) are only two.

This leads naturally to the biggest missed opportunity of the episode: any discussion of games as conveyors of narrative. This narrative, as I explained in our own Game Changers podcast, emerges from a unique synergy between what we in the Tabletop world call “theme” and “mechanics”. In the same way, narrative in graphic novels (as Scott McCloud forcefully argues in Understanding Comics), emerges from a unique alchemy of words and pictures which transcend their separate parts.

Humans seem to be wired to take in information better through stories, and I believe the continuing popularity of classic games like Chess, Go, and Contract Bridge is the compelling narrative that emerges from their gameplay despite their abstract nature. Chess and Go have distinct beginning, middle, and endgames–each with their own strategy and tactics, and Bridge has a two-act structure of bidding followed by trick-taking which has been copied so much because of its inherent suspense: will the contract be made, or not?

The “narraholism” of humanity also explains the continuing popularity of games which provide catharsis and immersion. Think of all those games based on beloved franchises, from Lord of the Rings to Star Wars to Harry Potter, and on through tabletop adaptations of popular videogames such as Fallout and Skyrim.

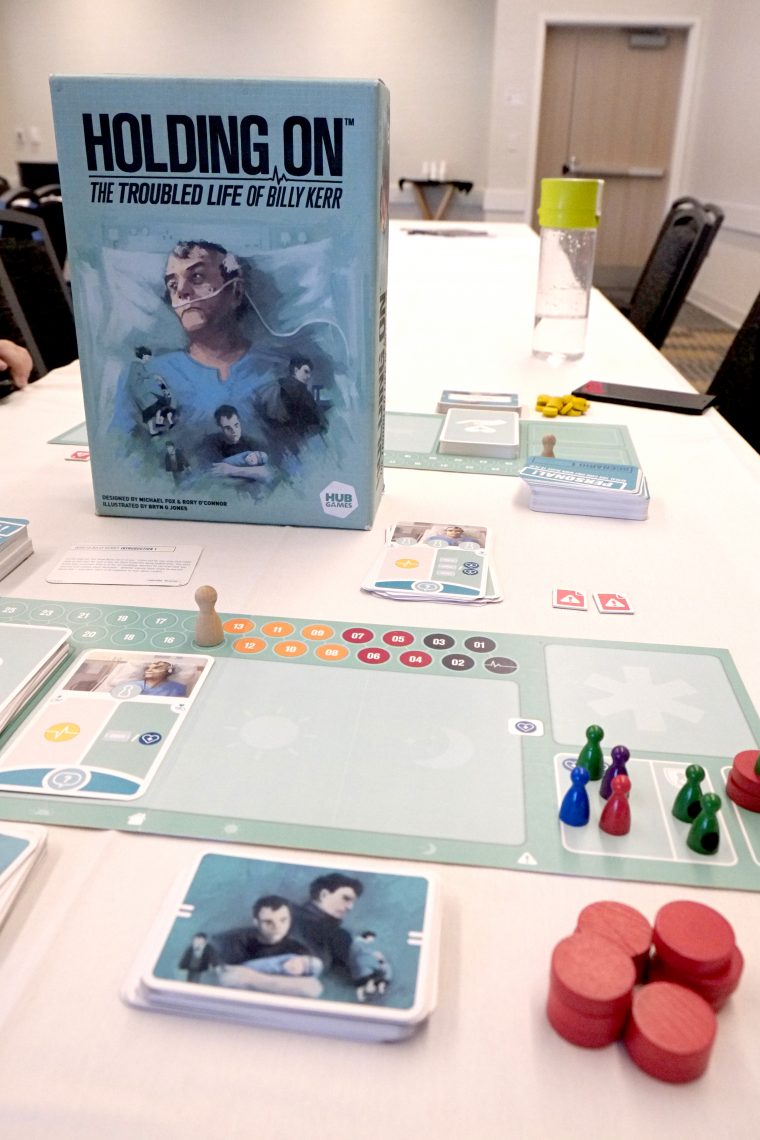

But there are also modern tabletop games which bring players together to work through difficult or problematic situations both historical (Freedom: The Underground Railroad, Stonewall Uprising) and fictional (Holding On: The Troubled Life of Billy Kerr, Heading Forward). These are also heroic stories but certainly not in the stereotypical swords, sorcery, and/or laserguns kind of way. Players come to these games to challenge themselves, sure, but I believe the primary motivation to play them must come from a place of wanting to experience a particular kind of narrative–the same way someone might get “pleasure” out of watching a movie like Nomadland.

This motivation even holds for games based on historical events where players know how the story ends, because there are always “what if” factors which beguile us with alternate outcomes: will nuclear war break out during Twilight Struggle? Will you manage to keep your tribe alive and intact in the face of Spanish and American incursion in Navajo Wars? Can you keep the country from splitting in two in Mr. President: The American Presidency 2001-2020?

Next I wish to address a more obviously Jungian theme: how tabletop games allow players to take on archetypal roles and characteristics in the service of the game’s narrative. Many co-operative games, from Pandemic to Sleeping Gods, give players unique special powers and actions which compel them to rely on and/or negotiate with each other to win the game.

Not only that, but as was observed in This Jungian Life, and something I wish to make more explicit, certain games give players permission to give rein to certain “shadow” aspects of their personality–for instance, The Trickster–in a (relatively) safe and structured environment. All hidden-role social-deduction games from Werewolf through to Blood on the Clocktower fall into this category, but don’t forget about classics like Diplomacy and I’m the Boss, which definitely reward a sociopathic “it’s only a game” mentality.

Here is as good a place as any to mention semi-cooperative games, where players are forced to work together to some extent against the game, but ultimately only one can win. Nemesis, Shadows Over Camelot, and Fog of Love are just three examples, and again look at the array of genres and settings used: Alien-infested spaceship; Arthurian England; modern-day rom-com.

There are games that explicitly use dreams, symbols, and their associations, which is a core concept of Jungian psychology. In Mysterium one player is the ghost of a murder victim and the other players are psychic detectives. The ghost and the players are trying to work together to solve the Clue-like details of the murder: the assailant; the weapon; the location. The twist is that the ghost may only communicate to the others through dreams, in the form of evocative picture-cards, which are given out to clue each detective to their individual “leads”. No talking from the ghost allowed!

Codenames is also about one person trying to clue teammates in to guess certain words as laid out in a random 5 x 5 array of cards. Again, communication is limited but this time clues are in the form of single words which the clue-giver hopes will tip off her team-mates to as many words in the array as possible using flexible thinking and association. Clue efficiency is crucial, because the other team is trying to pin down a different subset of the same array–and the team that identifies their words first is the winner.

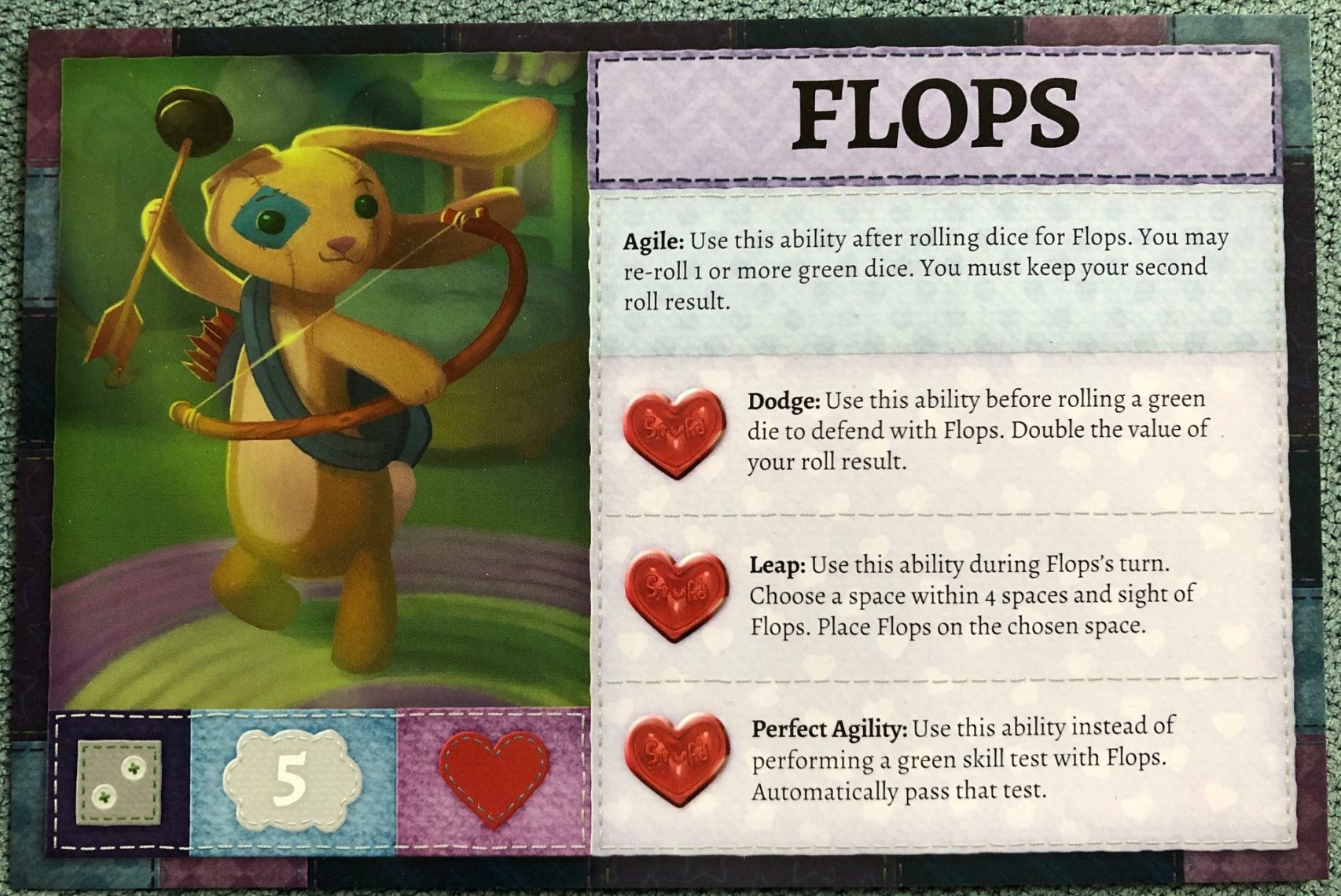

Finally, games like Stuffed Fables and Comanauts come closest to gamifying the therapeutic experience itself, as players enter the dream-worlds of a loved one to intervene and heal their psychic wounds.

As I hope I’ve shown This Jungian Life’s take on games is a good “first draft” but ultimately inadequate because they ultimately fail to see games as a distinct artform. Like sculpture, graphic novels, poetry, and cinema, tabletop games are sophisticated enough to manifest a wider variety of archetypes and experiences than the podcast acknowledges. And as with other cultural expressions humans use tabletop games, at both conscious and unconscious levels, to play out their individual and collective stories.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!