GMT first announced Mr President in the summer, 2014 edition of their “Inside GMT” Newsletter:

It is a solitaire game that puts you in the shoes of the President of the United States, attempting to govern, with limited resources, in a complex and ever-changing world. It is not a game about getting elected, and it definitely does not have a political affiliation or point of view. It is about GOVERNING, and the choices and trade-offs you make to try and balance keeping your citizens protected and happy while the world seems to be disintegrating all around you.

Mr President’s designer was none other than Gene Billingsley (the G in GMT). In the same article that announced the game, Billingsley pronounced it “the game I always wanted to design”. I’d actually never played any of his previous games. Starting with 1990’s Silver Bayonet, and on through the Next War series, Billingsley’s area of expertise was on the post-WWII era, and I didn’t play many wargames set after 1945.

This time though, I couldn’t hit the “pre-order” button fast enough. Like 90% of my fellow-citizens who live within 100 mi of the US border, American politics and culture has always been my jam. As Prime Minister Trudeau (the Elder) famously said in a speech to the Washington Press Club in 1969, “Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

Growing up, almost half of the cable stations available to me were American. Most of them were in the Buffalo area (Toronto being right across the lake), so even my favorite hockey team was not the Maple Leafs or Canadians but the Buffalo Sabres. I knew more American than Canadian history thanks to Schoolhouse Rock, and knew all the US Presidents by heart.

After the initial excitement of the announcement, though, Mr President seemed to fade from view. There were updates on the design, but after 2016, I found it harder to conceive of a game that would be able to reflect the heaving changes taking place in the American polity. I assumed that events had overtaken the game’s development. I gave up on it.

And yet, and yet…in 2022 we began to hear reports that Mr President was alive and well, and heading to the printer’s. Soon after, GMT charged my credit card for my eight-year-old pre-order and lo and behold, a couple of weeks later, I had a nine-pound baby on my doorstep:

The first thing you see when you open the game box is a letter from “Your Predecessor”. This immediately sets the right tone, making you feel like it’s your first day in office–just like every President since Bush the First.

Although the letter has zero gameplay effect, it does give you an excellent roadmap for what you should read first and how you should learn the game. Don’t try to second-guess this advice–even if you’ve watched one of Billingsley’s intro videos.

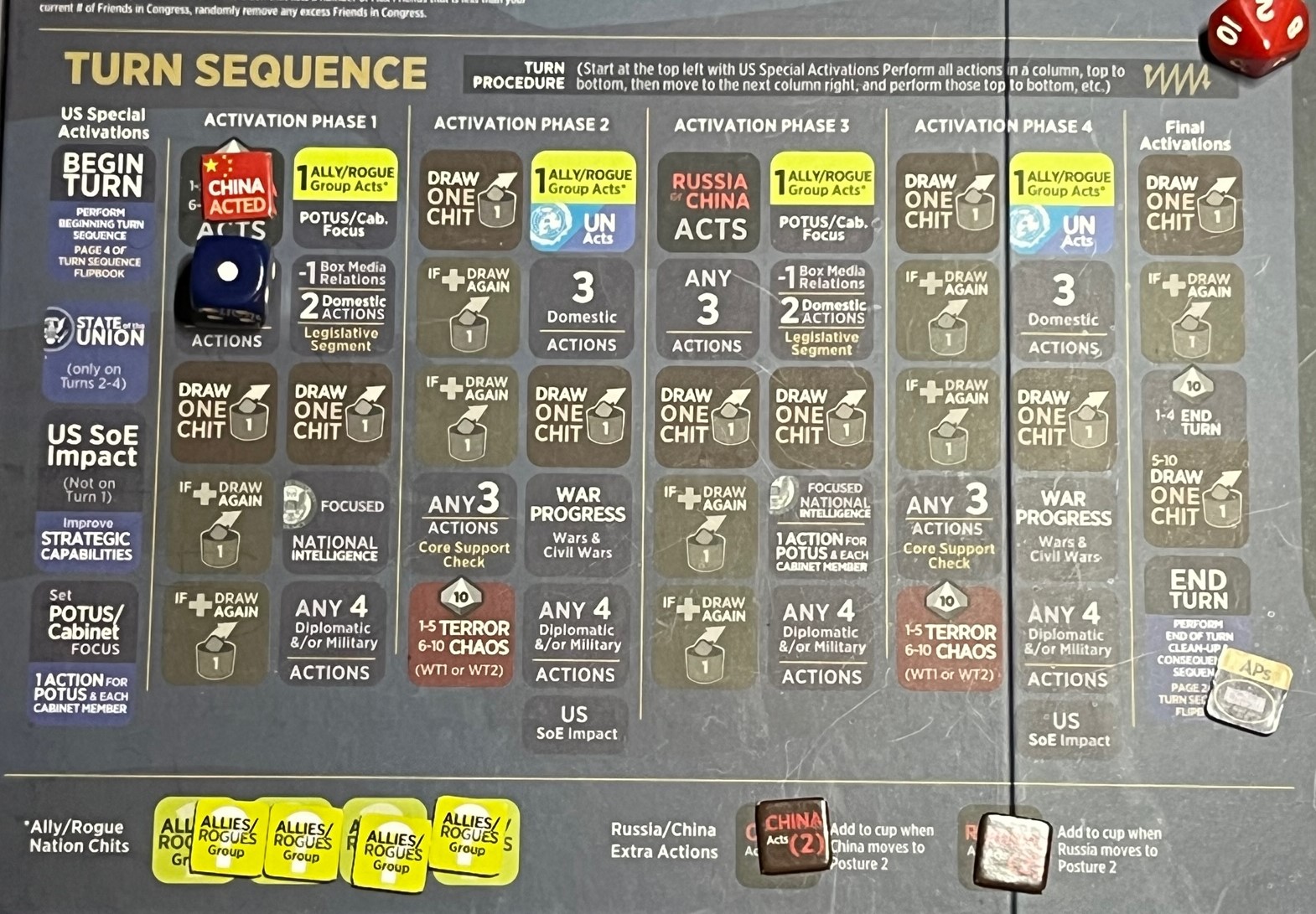

Soon enough you will set up the introductory Sandbox Scenario and come to the heart of the game: the Turn Sequence Flipbook. This is Billingsley’s masterstroke–and also a declaration of intent.

As he said in one of his early GMT articles (July, 2015) about the game:

I am not intending this to be a “beer and pretzels” surface level game. If that’s what you are looking for, RUN AWAY! 🙂 What I want is a game that is deep and immersive, one that will both frustrate and delight the solitaire player, an experience that will beckon you back to the game table after each round, turn, or completed game.

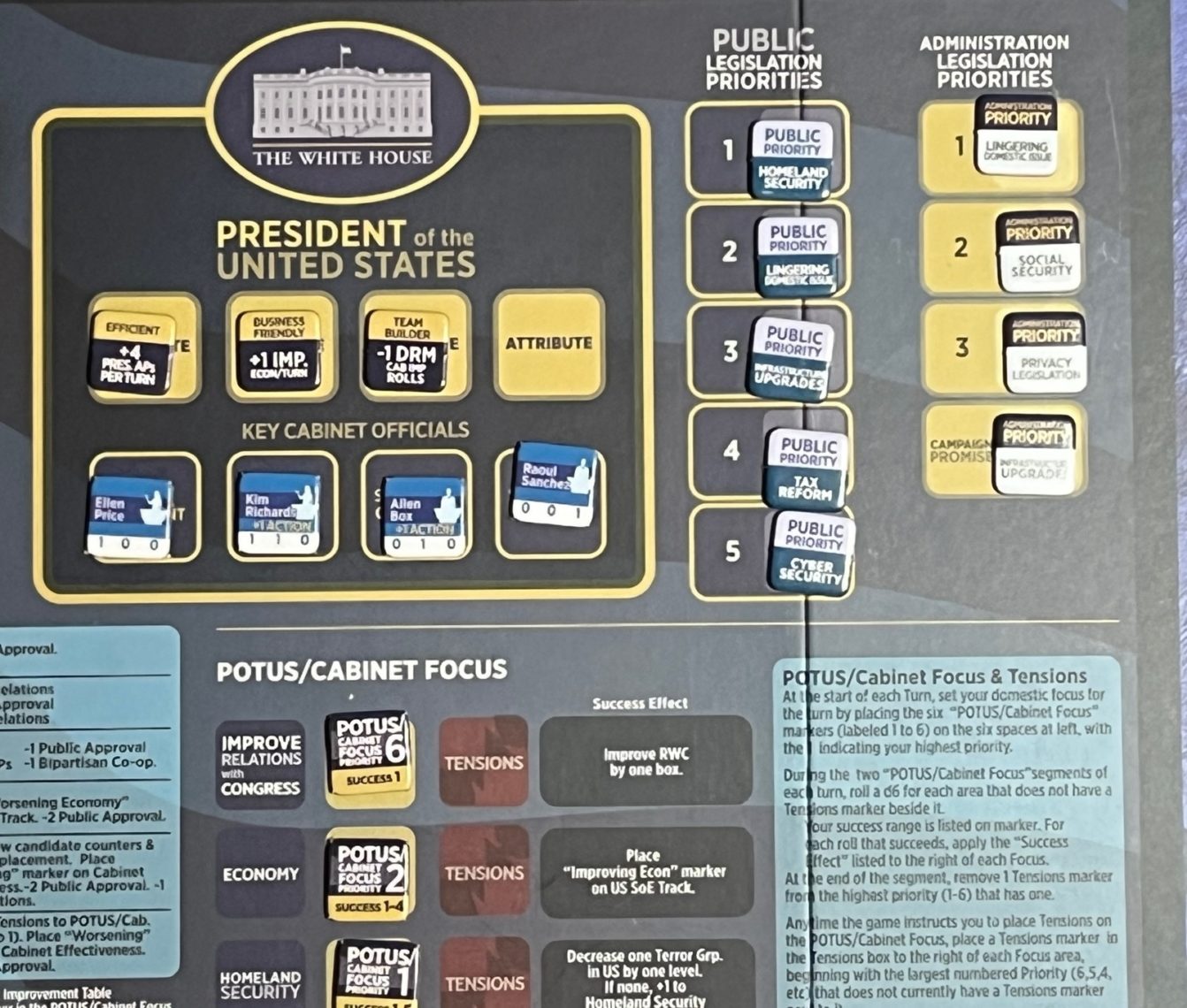

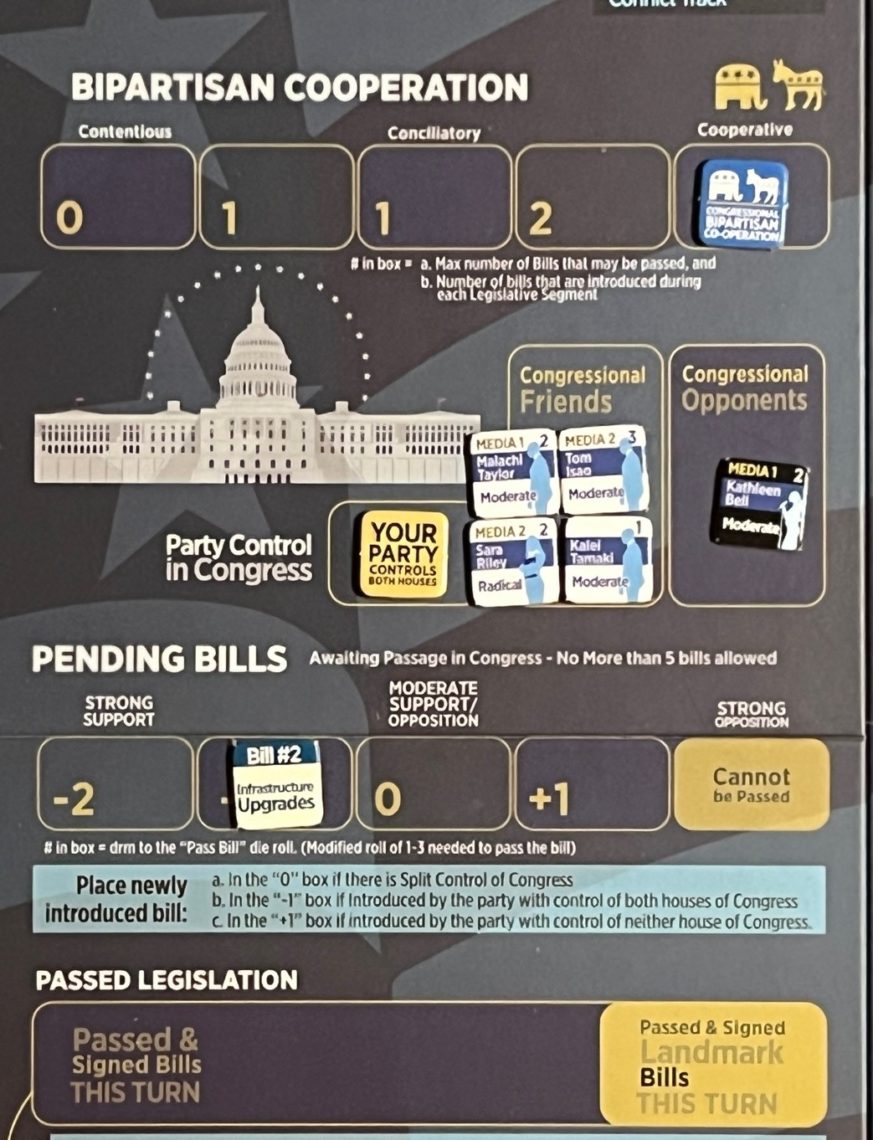

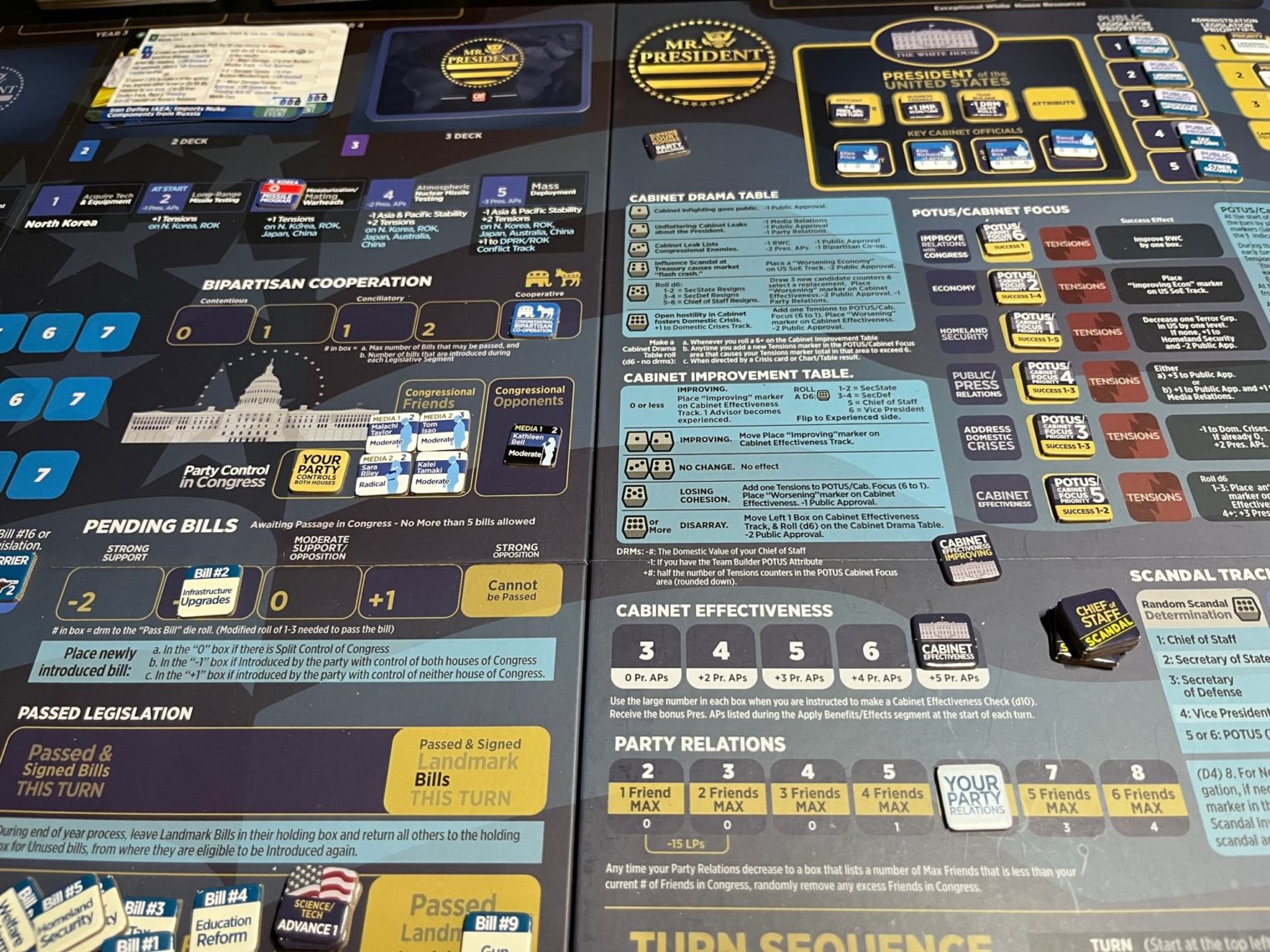

In the Designer’s Notes Billingsley calls Mr President a throwback to the “monster games” of the 1970’s, and as you can see from the above picture of how a turn proceeds–just one turn out of a potential four–this is not a simple game. Sure, he could have made it a lot more “elegant” and “streamlined”–but then it would have sacrificed a lot of the granularity which gives the game its immersion.

The downside to this is that the game has a huge footprint on the table, long setup and takedown times, and so many, many counters. To that extent, Mr President betrays having spent a lot of time being designed/developed on Tabletop Simulator, where the opportunity cost of adding more boardspace and chits is minimal. Oh, and don’t buy this game if you don’t like having to juggle multiple player aids and booklets.

That being said, I have never seen a game of this complexity put so much thought into “user experience”, such that it IS possible to literally set up the game and play it out of the box with almost no difficulty–I speak from personal experience. For that alone Mr President is a triumph of design. The board is organized so you can take in the state of play at a glance. The Turn Sequence Flipbook–which has many important tables reprinted therein so you don’t have to hunt them down. The game’s many charts are organized into separate booklets for easy lookup. The four player aids detailing all the game’s Main Actions are super user-friendly.

The Governing Manual functions like a Fantasy Flight Reference Guide: you probably won’t need to look at it at all until well into your first game. Generally it’s organized sequentially–ie, in the order that things come up in turn order, and if I do have a nit to pick I think maybe it should have followed the FF model all the way and just had everything alphabetized.

The rules have very few ambiguities, mistakes, or holes. The main one I encountered was what to do when “removing” counters, especially the crucial Tensions ones. But I posted to BGG and Billingsley answered almost right away (the answer: they are returned face-down and mixed back into the pool). And many of the page references on the back of the Governing Manual are just wrong–maybe stuff was reformatted at the last minute?

In some sense Mr President is the ultimate in Tower Defence, where “the Tower” is not necessarily the USA but instead your political survival. Every scenario but one requires you to have enough public support to be re-elected, and in the sandbox it is the only requirement. I’ll be returning to the implications of that later.

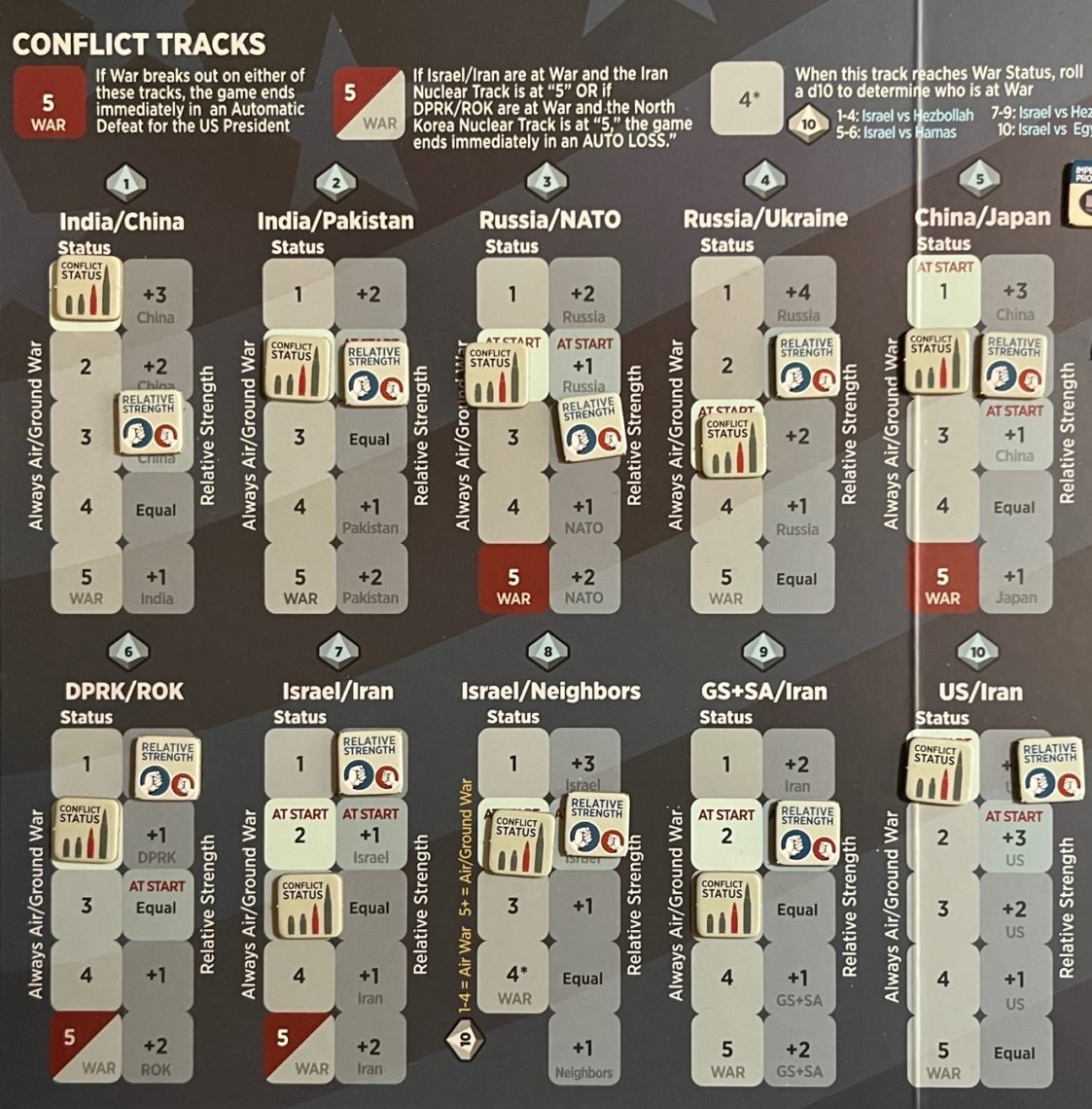

The “lanes of attack” on your “Tower” are numerous:

When it’s your turn to act, your menu of Actions depends on whether you’re acting as leader of your party, head of the Executive Branch, chief Diplomat, or Commander-in-Chief. You can try to marshal legislation through Congress, wrangle your Cabinet, stimulate the economy, visit an Ally to shore up relations, have a summit with Russia or China, spur military research, order drone strikes…and the list goes on. Sometimes you also need to spend a precious Action Point to make it happen or improve the odds, but in almost no cases are the results assured. You’re generally rolling a d6 or d10 against some ability level or situation track. If you fail playing at the game’s Easy level, you can expend more Action Points (AP’s) to reroll–and boy, is that something I wished I’d had playing at Normal (I didn’t even dare trying Hard).

Mastering the ebb-and-flow of the Turn Sequence is crucial if you want to have a chance for success in any of the game’s scenarios–and it’s also where the game as a simulation is most undermined. This is because you know when certain key events and threats (Russia, China, Ally actions, Rogue States, media relation decay, etc.) will definitely occur. It’s true that you don’t necessarily know which Allies and Rogue States will trigger, and that they may also possibly occur randomly due to events, but the fact that you have regular foreknowledge is definitely not realistic. This is a concession to gameplay that I am totally on-board with, but it’s worth pointing out.

I’m also unclear as to why different categories of actions are available at different times. Why only Domestic issues here and Diplomatic/Military there? One possible answer is that making all actions available anytime made things too easy. Another, ironically, is that this was actually done to help players focus on preventative actions for upcoming crises.

Those minor points aside, the game “feels” right to me, and the narrative that emerges from the interplay between all the game’s systems produces that “just one more phase” feeling that keeps you at the table, as the hours pass by. You don’t even have to play it solo: as Billingsley recounts in his Notes, the game is not only playable but enjoyable when played in a small group–possibly even assigning specific Cabinet responsibilities to particular players.

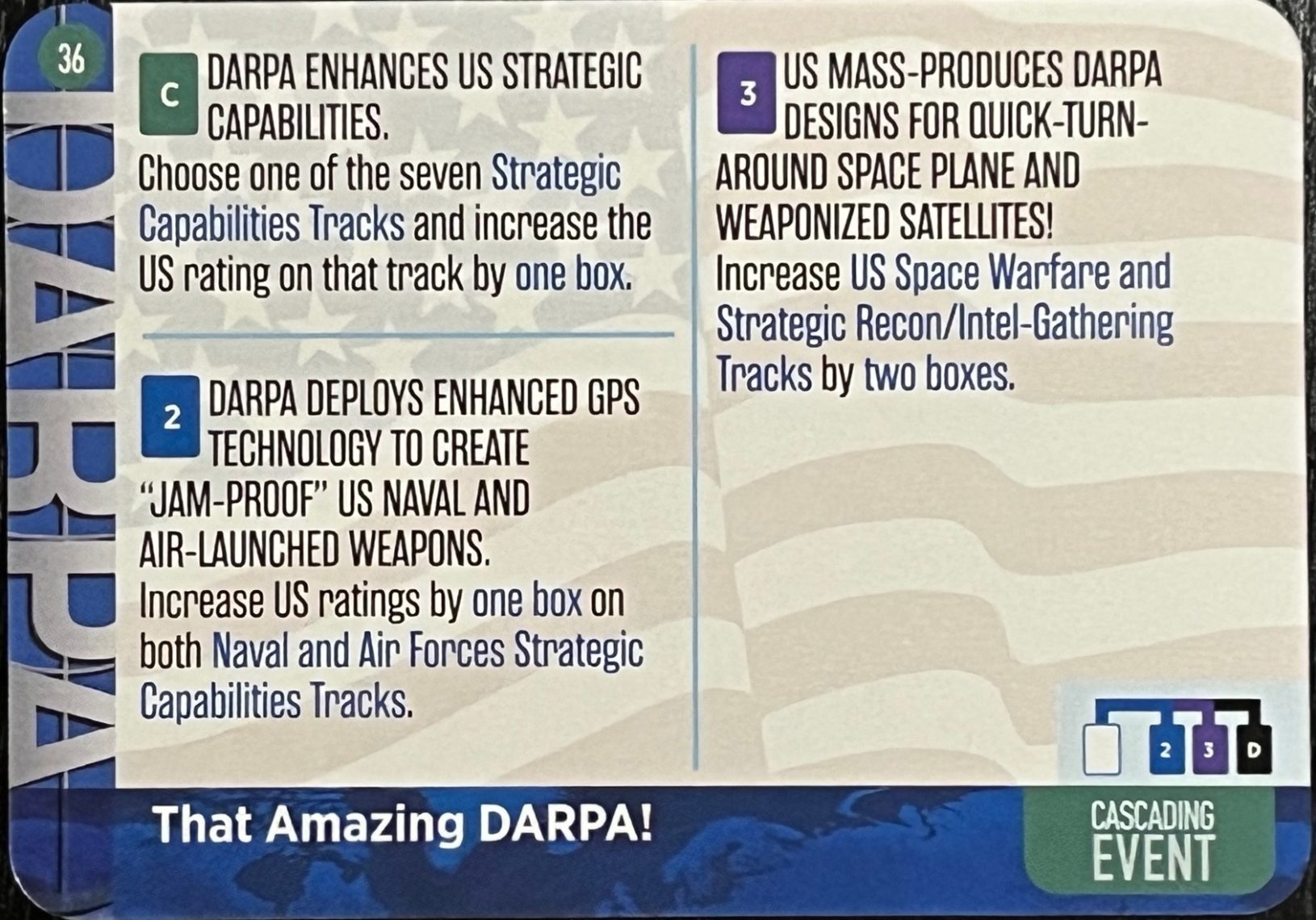

All in all Mr President definitely delivers on its promise, which is to make the player feel like they are, literally, in the President’s chair in the Oval Office. It is a milestone in game design and presentation. My favorite parts are assigning legislative priorities, running summits, and how Cascading events work. I can’t help but want expansions that would extend the game backwards in time to allow you to simulate presidencies from earlier in the 20th century.

But, being me, I can’t stop there. I have to ask myself what the game’s underlying message is. As much as Billingsley has tried to not have himself or the game seen as didactic (see below), you can’t play this game and not come away without what it has to say about the role of the American Presidency. What Mr President leaves in, what it models abstractly, and what it leaves out, all go toward what Billingsley wants players to focus on (or not).

On the surface level the game’s message is that (shock!) governing is hard. No matter what your good intentions are going in, it’s very hard to be proactive. The ship of state is huge and takes a long time to change direction. Most of the time you’re going to spend putting out fires (sometimes literally) and horsetrading. The game itself calls the process of getting legislation passed “how the sausage gets made”, which is a well-worn aphorism.

But underneath that surface lurk several riptides, the first of which is the role the United States has played since World War II (or the way it sees itself playing) as “the world’s policeman”. The game’s overt thesis is, as Tim Alabaster Smitty has said in his comments on BGG: “This is an unapologetically positive perspective on the U.S. presidency.” In Mr President you may inadvertently piss off an ally or make a regional crisis worse, but you would never do so intentionally, as a matter of policy…would you? If you’re looking for an ethically ambiguous take, you won’t find one in this game. It’s definitely more “West Wing” than “House of Cards”.

Furthermore, even with its positive outlook on the US’ global role, Mr President definitely conveys a feeling of imperial overstretch; there are never quite enough resources to keep all the various stakeholders (both domestic and foreign) happy.

The next dangerous underwater current is the flow of money–or rather the lack of it. Although American, European, Russian, and Chinese economies all have ratings that go up and down during the game, at no point are you (in any of your capacities) actually collecting or spending cash. No, I lie, party fundraising is mentioned at one point. But overall, dollars and cents are abstracted right out. There are no games of chicken with Congress over passing a budget. You never have to think about the cost of your various actions in monetary terms.

The reason for this is the Action Point (AP) system. At the beginning of each game year you receive an allotment of AP’s, and as the years go by they just…trickle away as you go about your business. Occasionally you earn some back due to various successful outcomes–which implies that AP’s also embody political as well as monetary capital. All this is brilliant from a design and gameplay perspective–but it also means you as President only really think about money as a political tool. In fact, all consequences of public policy are treated abstractly in this way. And how wonderful a way this is to portray a political class that is insulated from the real-world effects of its choices…

Now, Billingsley has taken great pains to present Mr President as a game that doesn’t “take sides”. Online he says:

I’ve gone to some lengths to try to keep Mr President from reflecting a partisan point of view, as I have no interest in being part of any game that would further the deep divisions we already have in this country around party loyalties, personalities, and platforms.

To say that I have tried to keep this game strictly non-partisan is not to say that it does not reflect some of my own beliefs about best practices. One of those is that “most of the worthwhile, lasting achievements in this world are accomplished by teams or partnerships of committed people.” I also believe that the best teams tend to utilize diverse team member backgrounds and points of view as wellsprings of strength rather than reasons for division. So in Mr President, the game interactions and results are indeed prejudiced toward you doing better when you work with others and not alone.

The table on page 27 of the flipbook where you compare your Legacy point total, Civilization-like, against previous Presidents only uses examples before 1960 “to avoid political bias”. So from Kennedy onward no one can agree who was good and who was bad, got it.

And in the Designer’s Notes he goes so far as to make a Hitman-like statement that the game was designed by (and is as good as it is because it is the product of) an inclusive group of people with diverse backgrounds and political views. Some might call this kind of commentary tactful and diplomatic.

Others might point out that Billingsley is well aware that GMT’s core audience skews (a) male, (b) older, (c) white, (d) right-wing, (e) military-minded, and possibly (f) MAGA, hence would tend to look unfavorably on a game (or a designer) who might challenge American exceptionalism, let alone try to expose systemic problems. And who wants to alienate potentially half their audience? I am reminded of the TikTok clip from Miss Americana where Taylor Swift pushes back on her father’s insistence that she not take a stand on the 2020 Presidential election.

The result is that, Mr President is the ultimate in both sides-ism–your political party doesn’t matter (ironically, Chomskyites would agree) and “radicalism” in both parties is treated equally. All legislation is neutrally coded: “Immigration Reform”; “Homeland Security”; “Gun Control”. The actual content of the law is left for you, the player, to insert if you want to. (I also note that abortion is not even included at all–perhaps that is the unnamed “lingering domestic issue”?) Your own feelings about these choices will undoubtedly depend on your own political leanings–but Mr President doesn’t want to know.

I just finished re-watching The Wire for the first time since the series finished fifteen years ago. As a portrait of pre-Obama-era America, it is without peer. The thesis of its main writers, Ed Burns and David Simon, was that the fundamental institutions of the United States–law enforcement (specifically the “war on drugs”); the legal system; unions; politics; education; media–were all dysfunctional and to some extent corrupt.

Mr President glosses over a lot of that. But, like Detective Lester Freamon in The Wire says, “All the pieces matter.” There is no boardgame like it. If you are at all interested in or passionate about American politics, you need to play it if not own it outright.

[…] President, Gene Billingsley. I went into this game extensively when it came out this past summer, so go there if you want my many thoughts. Suffice to say I still […]