Krakenlance never quite felt of his world, of his birthright. A worldly man stuck within the secluded kingdom of Atlantis, his life felt predetermined from the start: use the militaristic prowess he was endowed with and lead his soldiers and country to glory. If it wasn’t for Pliny the Elder’s vision of Vesuvius, this is where he’d be.

But Pliny was a knowledgeable man. A man who cared too much for the world and those around him. A man so daft he thought he could save them all. Trusting in the Goddess of the Underworld is quite the idiotic error for the only man who could see the impending doom of Vesuvius. Or… or was it?

The stories are unclear, as if they’re covered in the dust and ashes of a yet-erupted Vesuvius. Because we were saved. Somehow, some way, Pliny stopped the eruption. But his bargaining was lacking, because Pluto, Lord of the Underworld, had an addendum to add.

Mankind was given one year to fend off seven of Pluto’s scions – and defeat the Lord himself. Seven nations around the known and unknown world rose to the cause and sent their best.

Atlantis chose Krakenlance. This is his story.

Hoplomachus: Victorum is a solo-only, combat skirmish, campaign game set in the Hoplomachus system, which, in and of itself, is essentially a 1-vs-1 skirmish game loosely set in coliseums of the Roman era. Victorum instead takes place over four Acts, with each Act having a maximum of 12 days. Players will guide their chosen hero across eight different countries during those 48 days to defeat three Primuses and one Scion of Pluto, the overarching villain of this game’s lore. Each individual day sees the Hero and their party arriving at a new location and participating in a combat event, one that’s either for fun or to the death. Losing a particular day, or even set of days, does not end the campaign; rather, the only way to fail is to lose all units during an end-of-Act fight, or run out of Blessings (a.k.a your Hero’s lives). Otherwise, losses only slow down progress and growth, two features desperately needed in order to succeed in Victorum.

Now, I don’t normally do regular reviews. I don’t find joy in regurgitating rules and giving one paragraph as to why I think the game is good or bad. What I do find joy in is examining games to see why they click for me where others don’t. And Victorum is a brilliant use case for this, as I really have never enjoyed solo games or campaign games in the past. What makes Victorum tick? Why does this click with my brain so well compared to the other “more popular” titles in those mechanics?

But I am also writing this to gush about Victorum. I mean, I wrote a 200 word fanfiction to start this article that was all about my character and the world. C’mon.

Components, Organization, and Layout

Chip Theory Games, the designers and publishers of Victorum, design one type of game: those with poker chips, neoprene, PVC, and plastic. There are no paper or wood bits in this box, other than, well, the box.

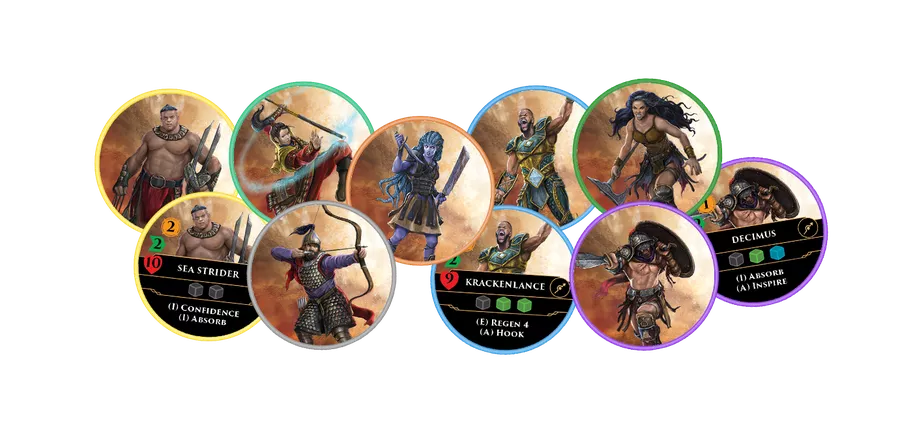

Regarding gameplay, the component quality mostly holds up and helps the game succeed. I know many have issued complaints at their products in the past for the sake of readability. While this production is improved over, say, Too Many Bones, it’s still sometimes difficult to read. Some complain that the combat units in the game being a poker chip with keywords on it is more work than it should be, as you have to reference a keyword sheet to see what the unit does. For my money, though, this is a common issue with most games that have combat units, as the idea of explaining what Taunt means on every unit that has Taunt sounds graphically busy and quite frustrating.

Honestly the biggest complaint I have with the readability of this game is the map. Again, at the start of each day in an Act, players will first move their party to a new location. While seeing these locations on the map, which is directly printed onto neoprene, is no issue, the lines connecting each place can be near impossible to read because the lines aren’t thick enough to properly translate onto neoprene. I know I have cheated at least once due to thinking there is a connecting line between two cities, only to check online later to find out I was seeing artifacts.

While the readability of the game can suffer slightly, the usability of the game more than makes up for it. A campaign game where there’s roughly 48 combat encounters is not one that will be completed in one sitting. Because of the use of chips and the way the game is both set up and stored, it is one of the few campaign games that’s actually easy to put away and get back out.

When I first set this game up, I never thought I was going to get to play it. Setting up my first campaign, when I knew nothing about the components in the box, felt like it took four hours to figure everything out. But resetting it after my first campaign took not even ten minutes. Set up and tear down while in a campaign takes less than five minutes due to the best non-gameplay component I’ve ever used: The colosseum seating.

Each region of the map has its own units that will be brought into battle when you have an encounter there, and will stick around for future encounters in an enemy drawbag. As the adventure begins, all of these chips rest inside of the colosseum seating for three reasons. One, it lets you clearly see the next unit from that region that will come into play, helping you decide if that’s a fight you wish to take on. Two, it lets the units be stored in between sessions so that these don’t have to be taken out and sorted each and every time (the lid for it actually acts as a way to prop the entire object up). Three, it’s thematic as all get out and really adds to the feel of the game. Not only does it feel like these combat events are being spectated by those around the region, but that I am being judged for my ability (or lack thereof). It’s absolutely brilliant.

Lastly, I want to call out the layout of the playspace. 90% of what you will be doing in the game takes place on the large neoprene mat that stretches on the table. Very few components (like the colosseum) rest outside of that. I have found this to be a really useful tool for determining how much space I need to play, as well as adding even more character to the whole experience: by focusing everything onto the one mat, I feel like a general staring down at battle plans instead of a nerd staring at a board game.

This category of layout and organization is where Victorum feels unmatched in many ways. Sure, there’s plenty of small box solo games that take up less room, but within the realm of larger solo games, nothing feels as compact and efficient as Victorum. Mage Knight and Nemo’s War have their charm, sure, but the sheer amount of set up time every single time you open the box, combined with the amount of space the game takes up, makes it difficult for me to want to get those out on a regular basis. However, it’s much simpler to unroll a mat and take three to five minutes to stack up some poker chips and place some decks of cards.

And part of the charm of Chip Theory Games, as much as others may be afraid to admit, is it adds to the enjoyment of a game when the pieces are fun to handle. Even though I own and love several Beige Trading German Euros, I cannot deny the fact that different textures, materials, and shapes do make the game more fun to manipulate. Especially neoprene. I’m such a sucker for some good neoprene.

Gameplay: The Travel Phase

At its most basic and stripped down, Victorum is a game about combat. Each day’s event is roughly going to be a 3 vs. 3, you controlling three of your units, and the AI controlling three of theirs. The turn structure is quite simple to grasp and even easy to remember: deploy a unit, play a tactic, move your unit, activate any abilities, fight. It’s only two and a half pages of the rulebook, and it’s what you do for most of the game.

That is not to imply for even a second that this game is easy. Far from it. But in order to unpack the difficulty in greater detail, I want to break down the overall flow of a given day in Victorum.

The first part of a day is the Travel Phase. During this phase, the player moves their party to a new location on the map, and have an encounter there. There’s so main factors to keep in mind here: the type of event, the continent that the event takes place on, and how many days are left in the Act, what Opportunities you have, etc. Let’s break down how much thought goes into each movement, starting with an overview of the event types.

There’s three types of events that can occur: Sporting Events, Bloodshed Events, and Opportunities. Sporting Events also come in three different flavors of objectives: Capture the Flag, King of the Hill, and Spars. In Capture the Flag, players have to move one of their units into the spawn location for the enemy team where the flag spawns, and then bring that flag back to their spawn hex. In King of the Hill, the player must leave their unit(s) on different hex(es), and if done so, score one point per hex at the start of their next turn, leading to victory at six total points. In a Spar event, the player must eliminate all of the enemy units except for one that gets marked as the Tribune, which must stay alive or else you will be punished.

Bloodshed Events are effectively just a Spar, with one added twist: there’s permadeath for your units. See, in a Sporting Event, the battle is, well, sporting. When a unit dies, there’s a presupposition that they’re actually just “tapping out” instead of perishing. During a Bloodshed Event, if someone runs out of health, they’re dead. They’re gone. They do not return to your camp.

These two event types have such a lovely symbiotic relationship to one another because of your rewards after completing an event. For instance, when you complete a Sporting Event, you have the choice to recruit one of the enemy units you just fought against. So, if you had a particularly brutal Bloodshed event, then you may want to try to go to and succeed at a couple of Sporting Events in a row to build up that roster that was so decimated a few days ago. On the inverse, if you’re doing well and you have a stacked roster, the best way to improve your party and improve your chances of winning the campaign is to not rest on your laurels, but rather participate in Bloodshed Events because all of the rewards for those events involve levelling up and improving your Hero, which is almost exclusively done from completing these events.

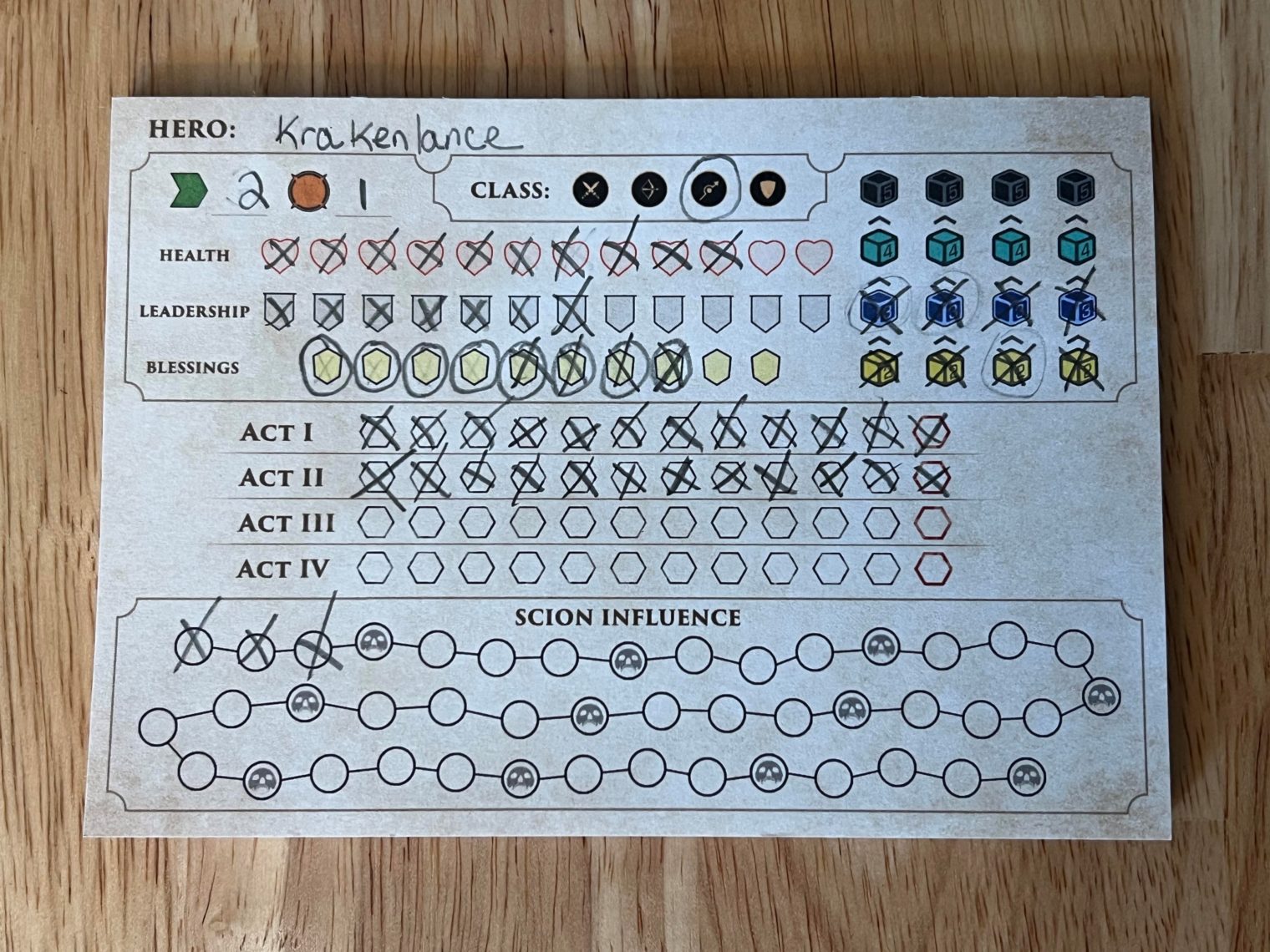

Speaking of which, let’s talk about the Heroes in this game. Your Hero truly is one-of-a-kind. Instead of your Hero being defined by pre-printed stats on its chip, your Hero is controlled by their stats on your campaign sheet. On this sheet, you track some aspects of the campaign itself, like which day of the campaign you’re currently on, but it’s also where you track the Hero’s max HP, Leadership (the number of units you can have at your camp, and by proxy, in your party), Blessings (your get-out-of-jail-free “lives”), and the dice they roll for combat. So, upon victory in a Bloodshed event, I can choose to raise my Hero’s stats. Do I want to make their health pool larger? Do I want to control more units? Do I want more dice to roll in combat? Do I want better dice to roll in combat?

In addition to the campaign sheet and improvements after a Bloodshed Event, Heroes can be improved through the third type of event, Opportunities. Opportunities often read like a sidequest: go here and do this thing to get a reward. Oftentimes these rewards come in the form of Prowess cards. Think of these like additional abilities that your Hero can gain. For instance, one of them for Krakenlance gives him additional abilities in combat, like making it so he grants additional dice to roll in combat for any adjacent allies.

Let’s take a step back again and talk about the very first thing you do at the start of a new day: choose where you’re going. Each location on the map is one of the three types of Events, so you know what’s on the line in regards to both potential loses, and potential gains. You have to keep in mind your party’s size, its strength, your Hero’s health (oh, did I mention their health doesn’t reset after each battle?), your Hero’s strength, where your Opportunities are pointing you… all while looking at the additional challenge and/or tweak the Sporting or Bloodshed Events have and them, and the enemy unit you know you’ll be facing.

Now, I know that’s all a lot. But don’t worry. There’s more.

Each continent has its own Arena. Not only are these aesthetically different (and their own neoprene mat), but they have their own unique rules and mechanics. For instance, in the Atlantien map, there is a Trident that the player’s units (and the enemy units) can pick up and throw across a long range for a decent attack. Some of these maps are much better for Sporting Events than Bloodshed Events, and vice versa. Some maps are horrible to bring your Hero out into, and some help your Hero thrive.

You’re having to take in the event type, event qualifier, continent map, your party, your Hero’s condition, and what your options will be for the following day, every single time you move. No Pun Included surmised that this was one of their many breaking points for the game, that there is too much to keep track of, and it leads to factors being missed, and more importantly, rules being missed (or having to spend too much time reading the rules).

For me, though, the first Act (the first twelve days) were rough and took time, but after I had those dozen or so days under my belt, this really doesn’t feel that overwhelming. Sure there are a lot of steps and factors to weigh against, but I think that’s exactly why I love this phase of the game so much. Having so many moving pieces and things to keep track of make it feel more closely aligned to a multiplayer board game instead of most solo ones.

Taking a step back from Victorum itself, I find most solo board games to be math-y puzzles, not games. Even games that many others would call dynamic and narrative focused like Mage Knight never felt that alive to me. There’s often a sense of “if I stare long enough, I will find the objectively best answer to my situation”. I don’t feel that Victorum has this issue because each possible positive benefit holds so much weight that each and every gain is crucial for success. Partner that with the randomness in the game via encounter set-ups, bag draws, dice rolling, etc., it’s never truly possible to see how beneficial a reward will be, as it’s never truly possible to know what’s coming up next.

Gameplay: The Event Phase

I can hear the Oscars Strings start to swell as this article gets long in the tooth. Don’t worry, I’m nearly there! Because for as much as this game adds to the solo and campaign spheres with its Travel Phase, the Event Phase where the combat takes place doesn’t really add much to its usual genre trappings. The combat is pretty simple. At the end of the day, this is a combat skirmish game with dice and keyword abilities: no one is reinventing the horse here.

There are some tweaks to the mechanics and usual gameplay trappings that I think truly help this game’s combat shine. The first is the dice themselves. A lot of skirmish games like this will have you roll a d6 and then assign hits on, say, a 4 or higher. This is perfectly fine, but I always found it so lacking. The amount of time and sorting that happens can take away from a climatic roll. Plus, as much as I hate to admit it, I really don’t like one of the most impactful game pieces to be as boring as a regular d6 when it’s surrounded by many other custom components. Finally, it’s so frustrating to have to level up characters and then remember that, because you’ve levelled up that unit, that it now hits on a 3 or higher, making the tedious process longer and more full of errors.

The way the entire Hoplomachus system fixes this issue is with colored dice. A blue die has three hit markers, and three misses. A yellow die has two hit markers, and four misses. A unit’s attack strength is marked by the colored dice. So, if a unit shows two blue dice and a yellow die, then there’s no more calculation: grab ’em and roll, look for the swords, and move on.

This may seem like such a small detail, but being able to offload any thinking in this game is crucial for its success since there’s so many other moving parts. With as much rolling as there is to do in this game, I can imagine that with regular d6s a combat encounter could be five minutes longer than it is, something that would make this game unplayable to me.

The last thing (promise!) I want to talk about with Victorum‘s systems deals with how loss is handled. As I mentioned in the introduction 2739 words ago, the campaign is only lost if you lose the final battle of any Act. Otherwise, individual losses are minor setbacks, through the use of what’s called Banes. These are often combat modifiers that help the enemy units/team, and/or hurt your units/team. Maybe it’s extra/less abilities, more/less health, more/less movement, etc.

Banes are acquired whenever your party does something really lame like have to rest or lose a battle. The absolute best thing about these penalties are how they are implemented into your campaign. Instead of taking place immediately, most are added into the enemy drawbag. As the game progresses, this bag will have more and more enemies added to it. At the end of my first campaign, the bag had roughly 30 units inside of it. So as these Banes start to build up and you take more and more losses as the battles get harder and harder, the unit composition in the bag also increases. Sure, the threat of the Banes are always there, but proportionally, you’re not necessarily more likely to draw them.

Couple that with the withdrawal mechanic: At any time in the game, you can withdraw from a battle. Besides not getting what you would from winning, your only penalties are tick marks towards your next Bane. This can lead to some obvious instances where withdrawal is better than sticking with the fight, where the fight is heavily stacked against you or your units are mismatched to the enemy’s. More often than not, though, it can lead to a lot of fun choices: “Do I want to take the chance to land the final blow against this enemy, giving them a chance to take me out if I miss? Or do I call the fight now and deal with the Bane later on?”

I cannot stress how much importance a fun loss state means to me with both skirmish and solo games. Skirmish games are often black-and-white, and quite punishing. Big losses out of (what feels like) nowhere, especially for someone as bad as I am at Ameritrash games, sucks. Here though, unless I’m playing Victorum on the hardest difficulty, I fully expect to get to the final boss no issue, if I’m keeping my wits about me. And that’s great. I’m here to play, and I’m here to engage with the campaign mechanics. If I died in Act I for my first ten attempts, I would sell the game. I want to see what the game can do!

As for other solo games, I’ve often found proper balance of loss hard to coalesce. If I’m playing some escalation game like Pandemic, I know when it’s over. I’m not going to play the game out, leading to me missing time with a game. Yeah, I could start another game, I get that, but I don’t get to engage with that “act”, that playstate since I’ll be starting at the very beginning again. On the other end, though, are the solo games with no tension at all. As much as it seems I’m not cool with Euro solo games, I do enjoy them when I’m in the mood. That’s Pretty Clever! has been played on my phone now roughly 100 times in the three days I’ve had it. But there’s no tension!! If I roll a bad number, I check a sub-optimal box and move on. Oh well. My high score is reduced. I still had fun, but the end-state isn’t victory. It’s like having Pineapple Upside-Down Cake: sure, it’s still cake, but, c’mon, really?

Conclusion:

If anything that I’ve written in this piece has gotten your attention, please take some more time to research the game. Usually I’d say go out and try it, but frankly, I ain’t about to recommend people spend $150 to try something. Here’s some additional, phenomenal reviews of Victorum (good and bad):

Mike from One Stop Co-op Shop

No Pun Included

Liz from Beyond Solitaire

Solo Designer Ricky Royal’s Playthrough

This is easily my favorite solo game, my favorite campaign game, and more than likely in my top 10 games ever. The flow of the game is buttery smooth, going from General-style planning to frontline fighting. Improving your Hero and your squad is satisfying beyond what I’ve felt in other games due to the sheer impact each and every tick of improvement has. The component quality is fantastic, and every piece has such weight and feel that it’s hard to put the game down. I can’t stop writing this article, because I want to keep adding more. Writing more. But I’m going to stop now. I bet I can fit in a quick encounter or two before I have to go to bed…

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!