In 2008, Donald X. Vaccharino revolutionized tabletop gaming with Dominion, which introduced the concept of deckbuilding. The mechanic was a stroke of genius, made Dominion a ten-expansion (and still-counting) franchise, and an instant fanboy out of me. I literally played over a thousand games of Dominion between 2008 and 2010, most of them online. Although the deckbuilding mechanic really clicked with me, after the first few expansions I got a bit tired of the generic medieval-ish theme. Plus, other games came along that took Vaccharino’s ideas and ran them to more interesting places, both thematically (Legendary, Harry Potter: Hogawarts Battle) and in terms of design (Xenon Profiteer, Valley of the Kings).

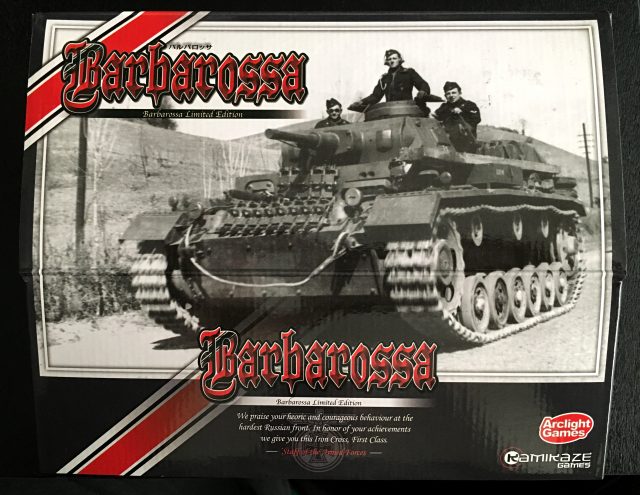

The spiritual descendant I’m going to talk about today, Barbarossa, was originally published by Arclight Games only two years after Dominion came out, but only in Japanese. A few imported copies made it over to North America, but Arclight got around to publishing an English edition in 2015. This was the edition I first played.

The spiritual descendant I’m going to talk about today, Barbarossa, was originally published by Arclight Games only two years after Dominion came out, but only in Japanese. A few imported copies made it over to North America, but Arclight got around to publishing an English edition in 2015. This was the edition I first played.

What drew me to the game initially was not only the mechanic, but also the theme, which is the Eastern Front of World War II. I’ve been playing wargames since I was ten, and have played half a dozen different games of the entire ’41-’45 campaign a total of at least, oh, a couple of dozen of times. If I throw in plays of games about individual battles and operations, I wouldn’t be surprised if the number tops one hundred. I don’t get off on the military gear, weapons, or ideologies; it’s the history and strategy that fascinates me. Plus my dad was a Holocaust survivor, so I’m sure part of it stems  from growing up with that hovering at the edges of my subconscious.

from growing up with that hovering at the edges of my subconscious.

(Some people question the morality of games which glorify war, particularly this war, and particularly this army. I know my dad definitely had trouble with ten-year-old me playing games with titles like Panzer Leader and The Rise and Decline of the Third Reich. This is indeed a thorny issue—and would make a good topic for a later article. Bear with me when I say I believe the glorification of war is not the droid we’re looking for right now.)

* * *

Barbarossa adheres to the most of the conventions established by Dominion. Weak initial deck, purchased cards go to discard pile, shuffle discard pile when draw deck is exhausted: check, check, check. Everything  has a different name (the central market is called the War Zone, Actions are called Tactics Points, Coppers are called Supply Points, etc. etc.), but the player-reference cards help you keep all the new names and icons straight. One little twist is that instead of having to discard the rest of your hand at the end of your turn, you can keep one card back, giving you an extra card on your next turn. Elegantly simulating battlefield planning, this turns out to give players a great degree of flexibility, and hence is a very useful (and often forgotten) rule.

has a different name (the central market is called the War Zone, Actions are called Tactics Points, Coppers are called Supply Points, etc. etc.), but the player-reference cards help you keep all the new names and icons straight. One little twist is that instead of having to discard the rest of your hand at the end of your turn, you can keep one card back, giving you an extra card on your next turn. Elegantly simulating battlefield planning, this turns out to give players a great degree of flexibility, and hence is a very useful (and often forgotten) rule.

The main changes to the deckbuilding trope in Barbarossa revolve around combat. Most of the cards you purchase will be Army cards giving you Attack Points which you need to capture Objectives. Many Army cards can be Deployed from your hand and stay on the table from turn to turn until either you chose to use them to capture an Objective or, sometimes, when an opposing player’s play forces you to discard or even return them to the War Zone (Schweinhund!).

Objective Cards are where most of your VPs are going to come from. Once during your turn, you can declare an attack. Minor Objectives aren’t worth much in terms of VP, but can be captured automatically as long as you have accumulated enough Attack points to match their target value.

Major Cities are where the lion’s share of VPs come from. They also have a target value, but when you attack them you also have to flip over and resolve the top card of an Event Deck, which usually boosts that value. This makes attacks against Major Cities riskier, because you may now no longer have enough Attack and will have expended your units for nothing.

Major Cities are where the lion’s share of VPs come from. They also have a target value, but when you attack them you also have to flip over and resolve the top card of an Event Deck, which usually boosts that value. This makes attacks against Major Cities riskier, because you may now no longer have enough Attack and will have expended your units for nothing.

Of course the rewards are greater, coming from both City and Event Cards, giving the player sehr, sehr viele VP’s and either reinforcements or the opportunity to put an obstacle in another player’s way. Objectives and most Event Cards are automatically Deployed, which means that, unlike Dominion, most VP cards do not sit in your deck like undigested bran.

The game ends when Moscow, the final Major City, is conquered. Players add VP’s from their conquered Objectives and add a sprinkling of VP’s from some Army cards in their decks (generally the most-expensive Panzer regiments). Highest total = Ubergeneral.

Although some might pooh-pooh the historicity of the game being non-cooperative, in fact there was a fair bit of politics and infighting between German generals, especially when it came to competing for supplies. The game also simulates the planning and logistics of war in surprisingly many ways. Besides the hold-one-back rule I mentioned above:

The game is not perfect. First, since you’re only allowed to attack once per turn, when the Objective Deck is down to one City and then Moscow (which is always the last card in the pile), there is no obvious incentive to capture the remaining City, because you’re leaving Moscow (and its fifteen juicy VPs) open for the next player to conquer and end the game. In a close game, where those 15 VPs will make the difference, play slows down instead of speeds up.

Second, there are more than twenty types of cards available in the War Zone—twice as much as a typical game of Dominion. Since the rules specify leaving out at most one pile, almost all card synergies will be open every time. Not to mention that twenty choices is pretty overwhelming. The designers clearly meant the replayability to stem from the randomness of the Major Objective and Event piles—which is not a wrong choice per se, but it does leave the door open to experiment with removing just one or two more piles from the War Zone to force players to experiment with different strategies.

Second, there are more than twenty types of cards available in the War Zone—twice as much as a typical game of Dominion. Since the rules specify leaving out at most one pile, almost all card synergies will be open every time. Not to mention that twenty choices is pretty overwhelming. The designers clearly meant the replayability to stem from the randomness of the Major Objective and Event piles—which is not a wrong choice per se, but it does leave the door open to experiment with removing just one or two more piles from the War Zone to force players to experiment with different strategies.

Lastly, the game lacks cooperative or solo options, although there is a solitaire variant posted on BGG which isn’t bad. This isn’t a flaw, but again begs out for some homegrown scenarios.

But all in all, Barbarossa is a very good deckbuild-y combat sim experience. If that is what you’re looking for, by all means seek it out.

You will want to think about which edition to buy, though.

The first Japanese and English editions of Barbarossa used original card art which can be charitably be described as “anime-style”. Later, Arclight re-released it using period photography and without flavour text. (They also decided to swap in a Gothic-style font for card titles and labels, which I think they did to make it more “historical” but which just makes the cards harder to read.)

It’s amazing to me how different the playing experience is between the editions, despite the fact that there are no differences in rules or card text (as you can see from the photos). To me, the boobalicious lingeriety of the original art is, at best, an unnecessary distraction, and at worst, a complete embarrassment—to the detriment of the game and to the point that I could only play it once before stuffing all the cards back in the box and hiding the box deep in my game shelf so my son couldn’t see it.

It’s amazing to me how different the playing experience is between the editions, despite the fact that there are no differences in rules or card text (as you can see from the photos). To me, the boobalicious lingeriety of the original art is, at best, an unnecessary distraction, and at worst, a complete embarrassment—to the detriment of the game and to the point that I could only play it once before stuffing all the cards back in the box and hiding the box deep in my game shelf so my son couldn’t see it.

Why why why, I kept and keep asking myself, would someone take a potentially-excellent game design and give it this kind of graphic design treatment? Is it just one of those “Japanese things”, the sort of cultural difference we are meant not to judge because…???

* * *

This next section is going to get a little serious—but it’s all in the service of this review, I promise.

About half a year ago my son was watching one of his favorite YouTube channels of the time, The Yogscast. As with many YouTubers, they came into  prominence with Minecraft videos, but as time went on they expanded into other videogame let’s-plays. I’m usually puttering around while he’s watching; sometimes I can’t help get sucked in by the audio of whatever he’s listening to. In this case, the Yogscast guys were playing through a dating sim—a choose-your-own-adventure-like genre very big in Japan. Though the settings vary, the general idea is that you play a single guy (or gal) who is trying to find love (or something quite like it).

prominence with Minecraft videos, but as time went on they expanded into other videogame let’s-plays. I’m usually puttering around while he’s watching; sometimes I can’t help get sucked in by the audio of whatever he’s listening to. In this case, the Yogscast guys were playing through a dating sim—a choose-your-own-adventure-like genre very big in Japan. Though the settings vary, the general idea is that you play a single guy (or gal) who is trying to find love (or something quite like it).

What is the appeal of such games? You might very well ask that. For adolescents with social anxiety who have spent a preponderant part of their childhoods in front of screens, I can see wanting to prepare for the complex world of adult relationships through playing these games. Or maybe it’s a way of safely experimenting in a virtual world with no real-life consequences. Or maybe it’s just an excuse to enjoy anime’s seamier underbelly, where women and young girls are portrayed in anatomically-unrealistic ways wearing scanty undergarments.

The dating sim in this video was something called Panzermadels. (If you want to see an animated 4-minute distillation of the playthrough, you can click here.) It’s a game available on Steam, where the setting seems to be some kind of tank school and the female cadets are also…tanks.

What I mean is that all the male characters are given human names and/or military ranks, but most of the female characters’ names are WWII-era tank names: M4 Sherman, Panzer IV, IS-2. And somehow, despite physically manifesting as typical anime-style females, they are in some unexplained-but-meant-to-be-obvious way, also…tanks.

The inherent surrealism of the story is definitely comical, on a surface level. So when one of the girl-tanks asks the Yogscast-player-protagonists, “Have you ever been in a tank?” their response (several seconds of total silence, followed by utter gobsmacked disbelieving snot-running laughter) is understandable. I admit it, I laughed, too.

But let’s unpack this a little, shall we?

First and worst of all, Panzermadels’ universe is the ultimate in the dehumanization and objectification of women. They literally assume the role of vehicles you can “get in”; how is that even?

Secondly, and thirdly, and to the nth degree-ly, what is up with the sexualisation of war, specifically? I guess it stems from the use of sexual repression and release by generals of every era to channel, manipulate, and control their troops. Soldiers give their weapons and vehicles women’s names. Airplanes and bombs decorated with Vargas-style pinups are an American art form. In its most extreme form, the use of rape as a tool of occupation is still happening, despite all attempts to wipe it out. It’s certainly no Japanese monopoly.

But what of the Japanese army in WWII, even more specifically? There’s some pretty horrible history there, such as the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Even allowing for the ignorance of today’s youth (regardless of nation or culture), the tankification of young girls screams out for some historical context. I can’t let it go by “just for funzies”.

* * *

So what about Barbarossa? The game is not a party or a “gateway” game; experienced deckbuilders will find it pretty straightforward, but newcomers will have to navigate plenty of new concepts and definitions. There are multiple paths to victory and much to keep track of while playing. And we’ve already established it’s pretty heavy theme-wise—we’re not merchants or traders, we’re wartime generals.

There is therefore nothing about the game that demanded the kind of cartoon-balloon-boob graphic treatment Arclight chose to give it. The titillation that the original art provides has as much to do with the actual game as the art of (American-made) vintage soft-porn playing cards has to do with poker. It’s hard for me to see it as anything other than as superfluous and envelope pushing for its own sake. Or, more harshly, as a cash-grab from collectors whose interest in the game goes no further than getting off on the card art.

There is therefore nothing about the game that demanded the kind of cartoon-balloon-boob graphic treatment Arclight chose to give it. The titillation that the original art provides has as much to do with the actual game as the art of (American-made) vintage soft-porn playing cards has to do with poker. It’s hard for me to see it as anything other than as superfluous and envelope pushing for its own sake. Or, more harshly, as a cash-grab from collectors whose interest in the game goes no further than getting off on the card art.

Me, I want tabletop gaming to be something inclusive, that will draw people in by the quality of the games and gorgeous graphic design. Needlessly-naughty art does nothing to further the hobby, and indeed provides fodder for those who condemn it because of the misogyny that lurks around its edges.

I’m glad Arclight chose to revisit their choice and republish the game with different card art. I bought the new edition as soon as copies were available here and, for me, the game experience is much improved and far less embarrassing and problematic. With its new edition, Barbarossa delivers on its promise of providing an Eastern Front deckbuilding experience.

Now I just have to figure out how to get rid of the first edition with a minimum of embarrassment and explanation.

The odds are pretty good, considering how the invasion went down, that there are actual rapists commemorated in the photos on the cards. The odds approach certainty that there are war-criminals depicted on the cards. This is preferable to boobalicious lingeriety?

What I don’t get is how every article has to be able buzzwords like “inclusivity” You could have easily written this article about “why can’t they make great games like this that I can play with my kids?” It’s a pretty simple argument – When you put boobs all over your cards, there’s a big section of the population that won’t play the game. If your goal, as a game company, is to sell as many copies as possible, why would you limit your audience right off the bat?

Not everything has to be about systematic oppression and rape imagery. It’s not “inclusive design” its “not deliberately off-putting design.” Nothing about the new cards draws anyone into the hobby (that would be inclusive) but it doesn’t immediately turn then away.

[…] games are a dime a dozen. Heck, I just wrote about one last week and again last month, and yet a third time about a dungeon delving […]

Maybe the card art is just supposed to be fun? Maybe some people prefer the bright and colorful look, as opposed to the drab and bleak look. Maybe some people want to play a fun card game, without being reminded of how terrible real war is, with actual war photos. Maybe your a little to sensitive when it comes to the topic of boobs.

It sounds like you come from the age, where women had to wear their underwear outside their clothes and on top of a thick sweater, in underwear commercials. And you never grew out of that time period.

Maybe you are looking into these things a little to deeply and serriously. Maybe a dating game about anime tank girls, is just supposed to be silly and fun, and has nothing to do with objectification. Maybe you need to get out of the 19450s.

I recommend expanding your horizons and opening up to the concept of new ideas. Maybe getting with the times, and letting go of past concepts like it being illegal for women to have boobs. Today is an age where things like My Horse Prince exists. Grow up.

If you dont like the art, sure thats fine. There is nothing wring with having different tastes, and not liking a specific art style. But dont try to insinuate that there is something wrong with it, simply because you dont like it. This world is filled with many many people, and some prefer cute anime girls over depressing war pics. And some people arent so sensitive, that seeing some cleavage, or some underwear, doesnt make them uncomfortable. Its as simple as that.