I was today years old when I found out that barrage had a non-artillery-related meaning. I’ve always pronounced it stressing the second syllable and drawing out the second short “a” and softening that “g”, giving it a French intonation.

But according to dictionary.com, when stressed on the first syllable, a barrage is “an artificial obstruction in a watercourse to increase the depth of the water, facilitate irrigation, etc.”

And that, dear readers, explains how Barrage–the game–got its name. It’s a bit of a gamble for a title because of its obscurity, but on the other hand I bet they were trying to avoid anything with “dam” in the title, for obvious reasons.

Because make no mistake, building dams is a big part of this game, designed by Tommaso Battista and Simone Luciani. This appears to be Battista’s first design, and his background in architecture and construction explains a lot about the game. Luciani is well-known for games like Grand Austria Hotel, Lorenzo il Magnifico, and Newton–as well as lighter family-oriented fare. Barrage, however, is definitely weighty–and not just in box size.

What’s interesting to me about Barrage is that it is not a super-heavy dreadnought of a game like Newton with mechanics piled upon mechanics. It’s pretty much “just” a worker-placement game. What makes it a brain-burner is the variety of the actions you can take and the intricacies of its two main actions.

Before delving into the gameplay, though, I want to mention the art-deco-style graphic design. It gives the game a kind of Bioshock vibe, which is either to your taste or it isn’t–and it also uses a font which is historically correct but awfully hard to read, especially given the dark palette. Luckily there’s no real reading to do off the board, and the iconography is clear and consistent.

The mapboards, on the other hand, are a model of usability. They portray a landscape ranging from mountains to hills to plains with four river systems cascading across and criss-crossing the board punctuated by basins. Understanding the way water flows around the map–and how you can reroute it by building your hydro systems–is key to victory.

Personally, I prefer the more functional “introductory” side with costs, conduits, and energy production spelled out clearly–but I’ll give props to the more “artistic” flipside with the same gameplay but more…um, I’ll say “pictorial”, with its monster-dams and spot-UV on all the water.

Players take the role of head architects of European nations, each with their own special power. Each has an assistant represented on a separate sideboard with their own special power, so you end up with Scythe-like mix-and-match combos which can switch up each game.

Barrage is played over five rounds. All but the final start with the headwaters being seeded with water according to random tiles selected at the game’s start. Each of the four will get between zero and two water drops, which are used to generate energy.

Players then get income, which depends on what they’ve built thus far in the game, Terra Mystica-style. After this is the meat of the game, the players taking turns placing engineers to take actions until everyone passes.

The most important actions are the energy-production actions. To generate electricity, a player needs to route one or more water drops from an owned or neutral dam (the game begins with three randomly placed so you can get going before building your own) through a conduit (built by anyone) to one of their power stations. The amount of energy produced is added to their total for the year and can also be used to complete contracts, which bring further bonuses.

Constructing dams, conduits, and power stations uses requires machines, time, and sometimes money. There are two types of machine in Barrage: excavators, which look like spiders; and concrete mixers, which look like Federation-class vessels. (I nicknamed’em, I didn’t design’em.) When you place your engineers on a construction action (you need more of them the more you construct every round), you don’t lose the machines. Instead, you place them into a sector of your circular production wheel. Those machines will not become available again until the wheel turns six times and spits them out. But you place the actual structure right away. There are ways to get that wheel to turn more quickly, like taking Workshop actions and fulfilling certain contracts–and you’re going to want to, because there aren’t many ways to acquire more machinery, and until the project is done you can’t build.

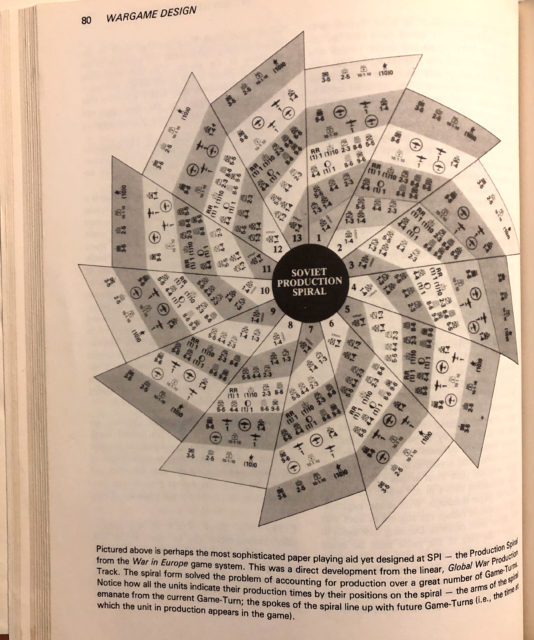

The funny thing is that while some people are over the moon about how innovative this construction system is, I haven’t the heart to tell them it was actually invented forty years ago for SPI’s monster game of World War II War in Europe which used an almost identical system (see the picture I’ve included).

But back to Barrage. Once you’ve produced energy with one of your power stations, the water you’ve used doesn’t stop there. After passing through the conduit and the power station, it keeps flowing, possibly having been routed sideways or even upward to a different river system, which means players with dams “downstream” from that power station stand to gain something later on.

These two actions (construction and production) are what makes Barrage so brain-bendy. You want to build your own dams to leech off of other players’ hydro systems–and try to avoid being leeched yourself. That, plus the fact that the number of hyrdro-producing actions is limited, means you’re constantly pinging back and forth between what to do next: do you grab a contract, or produce, or build something somewhere else?

After all the actions are done, the water flows. The water droplets begin their journeys from the headlands, following their river courses, accumulating behind dams where they will be used on future turns by players to generate energy.

Finally, players compare how much energy in total they were able to produce that round. On the first round it’s hard enough to reach the first point-scoring threshold of 6 units, but by the final rounds it’s definitely possible to produce more than 30 with all the bonuses. Whoever produced the most gets six points, second place gets two, and everyone gets a certain amount of money income based on how much they produced (money is very tight in Barrage). There is also a different end-of-round bonus (randomly set out each game) for all players that rewards things like contracts fulfilled, structures built, and so on. Then the energy meters are reset and play moves to the next round. On the last round there is a second endgame bonus (again, randomly determined) which rewards the top three players and is worth quite a passel of points.

And that’s just the basic game, folks. There’s a separate module in the base game which introduces production technologies that radically expand and reshape the construction process, letting you build things more often and more easily, or generating money or points.

I haven’t even scratched the surface of Barrage, let alone the Leeghwater Project expansion which adds another country to try (the Netherlands) and a whole new class of building you can build to give you even more to think about. Plus there’s the Automa system they included in the base game to make solo play not just possible but enjoyable and challenging.

I do know there was some legitimate dissatisfaction with the production of the KS copies of the game. All I can say is that the components of the retail version of Barrage are fine. Barrage is a great game. For me, it’s good to see a designer go deep with just one mechanic instead of trying to layer on five different ones. If you like heavier games, you should definitely check it out.

Thanks to Asmodee USA and Cranio Creations for providing a copy of Barrage for this review.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!