The news that Reiner Knizia’s L.A.M.A. had been nominated for Germany’s Spiel des Jahres was greeted by some with hoots of derision and general not-niceness. “All luck, play once and forget,” said some. “Boring, and ‘literally less choices than UNO!’” said another, in all caps.

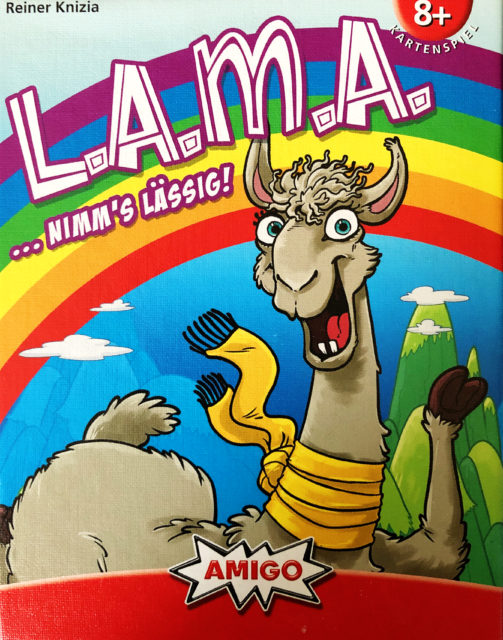

How little those stuck-up naysayers understand, dear readers. I don’t know about them, but my gaming group friends were almost instantly won over after just one or two rounds of this colourful little gem. L.A.M.A.–which is an acronym (in German) for “leave all your minus-points behind”–is indeed simple. It takes at most five minutes to explain. But the more you play it the more you see how, once again, The Good Doctor has encrypted a couple of layers of decision-making into the code for the game (metaphorically, I mean) which reveal themselves only to those paying attention.

Since minus points are sometimes tricky to deal with, I flip things around when I teach it and just say that, as with 6 nimmt or No Thanks!, the lowest score wins the game. I don’t know why Germans are more comfortable with negative integers than we are, maybe they just don’t play a lot of golf in Germany.

Everyone starts with a hand of six cards from a deck of fifty-six cards: eight each numbered one through six, plus eight llamas. One card starts in the discard pile. On your turn you must choose to do one (and only one) of the following things: draw a card; play a card; pass. If you pass you are out of the round and your score will be the sum of the remaining cards in your hand with two provisos: (1) llamas count as tens; (2) multiple cards of the same number count as only one card of that number. So if you pass with a four and three fives in your hand, your score will only be nine, not nineteen.

If you play a card it must be equal to or one greater than the card on top of the discard pile, with llama’s playable on sixes and ones playable on llama’s. Not many games are based on modulus seven but there you go.

At the end of the round you take counters from the bank equal to your score, with black counting as tens and white as one. You can make change any time you want (not obvious in the rules but clarified in the BGG forums). If you pass with no cards left in hand you get the additional bonus of giving back one counter to the bank–yes, a black one if you’ve got one. The game ends when someone hits forty points.

And them’s the rules. I normally don’t do rules in my writeups, but I did this time to emphasize that I agree how simple L.A.M.A. is. For the first play or two it does seem like your choices are obvious: play your highest-numbered singleton if possible, otherwise your highest value card; if not possible, draw a card, unless you can pass with a low number of points.

But there’s the rub. At all player levels, subtle strategies begin to reveal themselves. At first it may seem advantageous to be dealt a hand of same-numbered cards: it means you can pass with a low score (unless they’re all llamas!). But then you realize that this limits your flexibility, since you can get rid of a card only some of the time. Next is estimating what number is likely to be at the top of the discard by the time play gets back to you (and therefore what value card you need to have ready). In two-player games, that’s easy to know, since it will be at most one higher; the more players there are, the more uncertain you get. However, there will still be an upper bound, since you can calculate what would happen if every player plays the next-higher value.

This means that it is not always advantageous to simply get rid of singletons right away, as the lack of that value may constrain you later in the round. Much depends on context: how many players have passed, how many cards people have left in hand, and so on.

One thing I find is that, with good players, it can take quite a few rounds for someone’s score to get to forty, because of the up-and-down nature of scoring. I played one game where someone was at thirty-nine and then managed to go out, which reduced his score to twenty-nine, and we had to play several more rounds before someone else went over. You might try lowering the trigger score to thirty once players have begun to master the intricacies.

I’m not trying to pretend L.A.M.A. is a heavy game or a brain-burner. It’s not. It’s a casual game with plenty of larfs in it as players dare each other to draw or pass suddenly, leaving the remainder in an unexpected lurch. But there’s more “there” there than meets the eye, and I love games like that. You know, “minutes to learn, a lifetime to master”. For now L.A.M.A. is only available as an import, but I hope soon local Toronto stores will be carrying it, and you should definitely check it out.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!