Last week I took on the meaty task of providing an overview of premier designer Martin Wallace’s main themes: trains; history; military conflict. These three themes overlap and interlace, and several games (say, Brass) belong in more than one category.

This week I want to look at some of the “odd ducks” of the Martin oeuvre–games that, when you look at them and play them, and then find out it’s a Martin Wallace game, you think, “This is a Martin Wallace Game?”

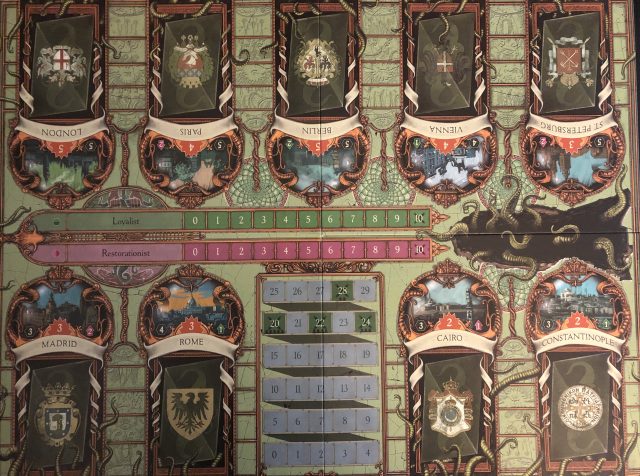

When I picked this up at the store in December I read the text on the back of the box and thought, “Huh, a card-driven fantasy-themed game with uniquely-powered factions racing to collect gems and/or knock everyone else out. And the designer is…Martin Wallace?

And furthermore, the damn thing works, and works well. You start by drafting starting positions for your team of four–and the locations you don’t pick become gems the other player(s) are trying to pick up. So, interesting decisions right off the bat. Each faction has its own deck of cards, which have multiple uses. Each faction plays differently: some are in-your-face melee, others specialize in ranged attacks, or speediness, or just messing with you. One nice touch is that the board starts empty, and each turn you have to spawn in one of your fighters, which ratchets up the tension nicely, and makes for some fun “where the heck did you come from?” moments. With two players, it’s chess-like positioning. With four, it’s a knife fight in a phone booth. Expansion factions and boards are already in the works. Wow.

Keep in mind that the games I’ve covered over the past two weeks don’t even represent even a quarter of Wallace’s output. Wallace has a deft touch for finding elegant ways to incorporate theme into his games. The quality and quantity of Wallace’s output and his versatility are truly mind-blowing.

And yet…

Despite being one of the undisputed name-above-the-title designers of the tabletop world, Martin Wallace has two related weaknesses which lead some gamers to keep his new designs at arms length:

Issues with the Rules

Right from the start (see Way out West, above) there have been complaints about Wallace’s rules-writing. In general one could say that his rulebooks are generally brief and to the point. This would be a plus if they were complete. However, he consistently words key rules assuming players will infer the correct interpretation from elsewhere in the manual. An example of this is in Lincoln, his most recent design, where much depends on understanding how locations on the board are considered to be controlled by one side or the other. Each city is split into two sub-sections, and either player can move/deploy to either side under certain circumstances. Knowing when you may or may not move into or trace supply through a city is key to winning the game, but the rules are frustratingly vague.

Other rules issues stem from what mathematicians would call “edge cases”. Every game has unusual situations which are not covered by the regular ruleset. These require special rules to keep the game from breaking. An example of this is the “ko” rule from Go which prevents an infinite loop of capturing. Other times two rules collide or even contradict each other and require some kind of ruling to give precedence to one or the other. Examples of this abound in CCG’s like Magic: the Gathering where you have to know which keyword on which card triggers first.

There are many examples of missing edge-case or priority-ruling rules in Wallace’s games. For instance, in this thread there’s a long discussion whether it is legal in Liberté to play a card in a certain situation. There is a lot of back-and-forth about the specific wording in the rules, and even some spillover into other rules.

These are cases which could (and should) have come up in playtesting and then been dealt with directly when writing the rules. Obviously you can’t cover all unusual cases, but compared to the standard out there, Wallace’s rules (at least the ones put out under his own Treefrog label) fall below the mark. You don’t want to spend two hours playing a one hour game because you’re spending half your time either debating or researching the rules.

But vaguely-worded rules are not the only consequence of inadequate playtesting…

Balance Issues

Given Wallace’s productivity, I can only imagine what a typical day in his life consists of. He must have a huge number of playtesters at his beck and call to ensure quality control, right? Well, I don’t know about that. I could go back and look at the credits to all his games and count the number of different playtesters he’s used, but the kindest thing one can say is that Wallace is not afraid to go back to his designs and tweak them to get them right. An unkinder thing one could say is that a few of his games, even major releases, seem to hit the ground broken.

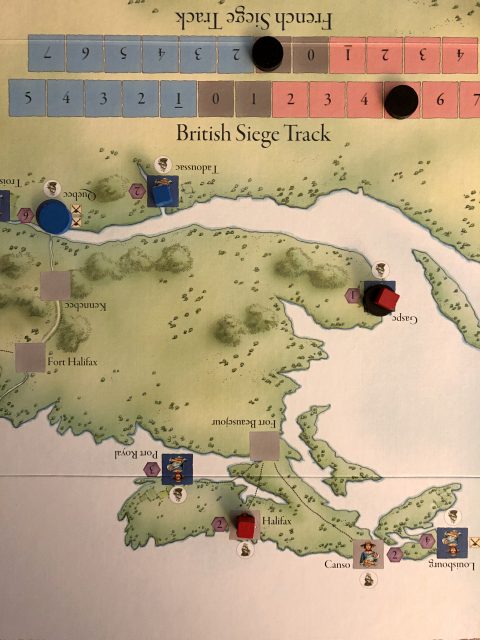

The most infamous case is A Few Acres of Snow, which is a game about the Seven Years War in North America using deckbuilding. This was a highly-anticipated release (including by me) and when it came out I enjoyed it highly. Then I started to see posts on this thread on BGG which claimed that the British had an unbeatable strategy (dubbed the Halifax Hammer).

The thread goes on for 36 pages. The general consensus was: yes, with the rules as written, the French were basically done for. People (including me) piped up with suggestions for changes, but it was only eight months later that Wallace chimed in with a hotfix that nerfed the Hammer.

Hardcore players felt the game was still broken. I was satisfied, but the game’s rep was tarnished forever after that. The thing of it was, the Hammer was a pretty obvious strategy once you’d absorbed the rules and played the game a bit. Why hadn’t playtesters found it?

When Lincoln was Kickstarted, the same thing almost happened all over again when Kickstarter backers noted that the Union side was vulnerable to a sudden-death loss whereby the Rebels capture Washington; this strategy was cheekily named The Manassas Mauler. Luckily, since the game had not yet entered production, Wallace was able to make the changes before the game was released this time, and despite the rules issues (see above) I think Lincoln is a good little American-Civil-War-themed game.

Because of issues like this some fans would rather sit on their hands and wait for a second edition of a Wallace game rather than have to deal with a flawed (or broken) game which requires multiple trips to BGG to get to a playable condition. It is therefore heartening to hear that Wallace has decided to wind down his own publishing company and concentrate on design (see http://www.treefroggames.com/ for more). I believe he is right to leave the production and marketing to others and spend his time on his core strength, which is designing great games.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!