Mankind has been playing games for at least 5,000 years. Entire civilizations have risen from obscurity to dominance and collapsed again in that span and still games remain. From ancient Mesopotamia to modern Japan and from sub-Saharan Africa to the  snow-swept tundra of the Arctic Circle, games have been a constant in human civilization. The earliest games were abstract in nature – Senet, Ur, Mancala, Chess, Go, Backgammon, and many others. Abstract games have no themes or narrative, just rules and pieces that provide a way to determine victory. Many of these ancient games have disappeared, lost to time, but some survived the centuries and new games have risen to take the place of the lost ones. Modern designers are still creating new abstract games. The purity of the genre attracts many designers and players, and allows for some really excellent app implementations as well.

snow-swept tundra of the Arctic Circle, games have been a constant in human civilization. The earliest games were abstract in nature – Senet, Ur, Mancala, Chess, Go, Backgammon, and many others. Abstract games have no themes or narrative, just rules and pieces that provide a way to determine victory. Many of these ancient games have disappeared, lost to time, but some survived the centuries and new games have risen to take the place of the lost ones. Modern designers are still creating new abstract games. The purity of the genre attracts many designers and players, and allows for some really excellent app implementations as well.

Everybody knows Chess. The language and imagery of this ancient game has permeated our culture. Comedians make jokes about priests moving on diagonals, “checkmate” has come to mean victory in any conflict one might encounter, and the games even inspired a major Broadway musical. Chess has spawned a number of imitators and variations, and countless games are inspired by its concepts and  elegance. No modern game that traces its roots to Chess is better, in my mind, than the Duke, from Catalyst Game Labs and designers Jeremy Holcomb and Stephen McLaughlin. It takes the basic ideas of pieces moving on a grid in their own unique ways and capturing your opponent’s leader, and throws in some twists that make the game outstanding. Pieces are flat tiles with their movement options printed right on them. This means players never have to memorize all the moves a piece can make. The tiles are also double sided, with different moves on each side. Every time you move a piece, you flip it over so it will do something different the next time you use it. The other mechanic that flat tiles allows is the random drawing of pieces. Unlike Chess, where you have all your pieces set up in a standard pattern at the beginning, in The Duke, players begin the game with most of their pieces in a draw bag. On your turn you either move a piece or you draw a new one and place it next to your Duke. The Duke has several expansions on the market, as well as a sister game, Jarl, that draws additional inspiration from the asymmetrical Icelandic game Hnefatafl.

elegance. No modern game that traces its roots to Chess is better, in my mind, than the Duke, from Catalyst Game Labs and designers Jeremy Holcomb and Stephen McLaughlin. It takes the basic ideas of pieces moving on a grid in their own unique ways and capturing your opponent’s leader, and throws in some twists that make the game outstanding. Pieces are flat tiles with their movement options printed right on them. This means players never have to memorize all the moves a piece can make. The tiles are also double sided, with different moves on each side. Every time you move a piece, you flip it over so it will do something different the next time you use it. The other mechanic that flat tiles allows is the random drawing of pieces. Unlike Chess, where you have all your pieces set up in a standard pattern at the beginning, in The Duke, players begin the game with most of their pieces in a draw bag. On your turn you either move a piece or you draw a new one and place it next to your Duke. The Duke has several expansions on the market, as well as a sister game, Jarl, that draws additional inspiration from the asymmetrical Icelandic game Hnefatafl.

Reiner Knizia is one of Germany’s most prolific game designers, with a huge list of hits to his name. One of his best abstract games is Fantasy Flight’s Ingenious. Ingenious is a tile-laying game in which players earn points by playing matching symbols on the board, a little like Dominoes. The bigger the area of matching pieces, the more  points are scored. There are six different symbols that players can score points for, and true to Knizia’s style, the symbol you score the worst in is the score you use to determine victory. Ingenious is a Mensa Select award winner and is available in a full-sized edition, and a smaller travel edition. The biggest criticism of Knizia’s work tends to be that even his themed games (such as Ra, or Tigress & Euphrates) tend to be pretty abstract with the themes thinly pasted on in an effort to sell more copies. Other excellent abstract Knizia titles to try include Indigo and Qin.

points are scored. There are six different symbols that players can score points for, and true to Knizia’s style, the symbol you score the worst in is the score you use to determine victory. Ingenious is a Mensa Select award winner and is available in a full-sized edition, and a smaller travel edition. The biggest criticism of Knizia’s work tends to be that even his themed games (such as Ra, or Tigress & Euphrates) tend to be pretty abstract with the themes thinly pasted on in an effort to sell more copies. Other excellent abstract Knizia titles to try include Indigo and Qin.

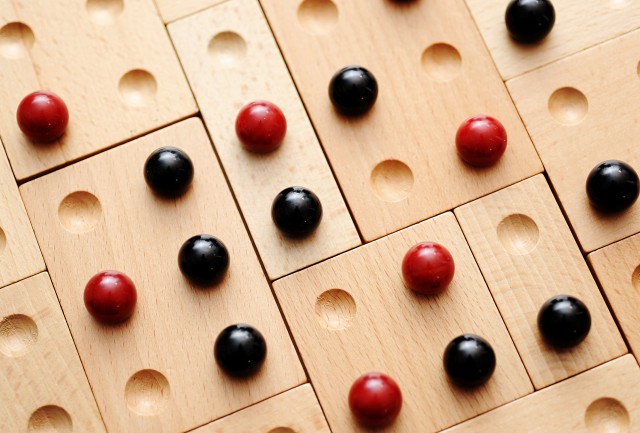

Abalone is an older, but still modern game for two players. The pieces are marbles on a board made of grooves and divots. Players make moves by pushing their marbles in rows, in an effort to force their opponent’s marbles off the board. A move can be one, two or three of your marbles, and you can only push your opponent’s pieces if your move outnumbers their pieces. The first player to lose six marbles loses the game. The simple rules and depth of strategy make this game a great addition to the genre.

Kulami is another exceptional two-player abstract game with simple to learn rules and challenging to master strategies. The game is different every time you play, because the board is modular – you create the playing field before each game. Each piece of the game board is worth points to the player who controls it at the end of the game. Control is determined by who has placed more of their stones on a board segment. Players take turns placing stones on the board, with their moves constrained by their opponent’s previous move. This is another award winner that more people should be playing.

Kulami is another exceptional two-player abstract game with simple to learn rules and challenging to master strategies. The game is different every time you play, because the board is modular – you create the playing field before each game. Each piece of the game board is worth points to the player who controls it at the end of the game. Control is determined by who has placed more of their stones on a board segment. Players take turns placing stones on the board, with their moves constrained by their opponent’s previous move. This is another award winner that more people should be playing.

Susan McKinley Ross’ Qwirkle, originally released back in 2006, was 2011’s winner of the prestigious Spiel des Jahres award, when it was finally released in Germany. Imagine Scrabble without words. Instead of laying letter tiles on the board to make words, players play coloured symbols to create rows and columns that obey the rules and allow them to score points. Each row and column must either contain all different shapes but no different colours, or all different colours and the same shape. The longer the row, the more points earned. By completing a line of six tiles (the maximum possible length), you also score a bonus six points. Qwirkle has a regular and travel editions, as well as a dice-based version called Qwirkle Cubes.

Coloretto, by Michael Schacht, is one of my favourite abstract card games. People don’t often think of card games as being abstract, but in truth, the vast majority of them are. In Coloretto, players compete to score points by collecting cards of various colours. The catch is that you only score positive points for the three colours that you have the most of in your collection. All colours beyond your top three cause you to lose points. At the start of the game there will be a number of empty card piles equal to the number of players playing. On your turn you either draw a card from the deck and add it to a card pile, or you take a pile that has at least one card in it. Piles can hold a maximum of three cards. if it is your turn and all the piles are full, you must take one. Once everyone has taken a pile, the round is over and a new round begins. when the deck reaches the end point, players score points. After playing through the deck three times, the player with the highest score wins. The key to this excellent game is poisoning card piles that your opponents might want and taking a pile before your opponents can poison what you want. Great for up to five players.

Perhaps my all-time favourite abstract card game is No Thanks! by Thorsten Gimmler. It is big bundle of contradictions in a tiny box. It’s a point scoring game, but like golf, lowest score wins. It’s a card collecting game where, ideally, you won’t take any cards. It’s also an auction game, but instead of paying to take what you want, you pay to avoid taking things. Fantastic and fast, it’s an easy game for anyone to grasp.

Perhaps my all-time favourite abstract card game is No Thanks! by Thorsten Gimmler. It is big bundle of contradictions in a tiny box. It’s a point scoring game, but like golf, lowest score wins. It’s a card collecting game where, ideally, you won’t take any cards. It’s also an auction game, but instead of paying to take what you want, you pay to avoid taking things. Fantastic and fast, it’s an easy game for anyone to grasp.

This list will get you well on the way to loving abstract games, but you should also try Yinsh, Iota, Hive, Yamslam, Onitama and Patchwork (yes, Patchwork is about quilting, but it’s about quilting in the same way that Charlie’s Angels was about law enforcement).

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!