Everything about The Shores of Tripoli shows just how influential GMT has become. Let me explain:

This is the box cover of the first wargame I ever played (1974’s Panzer Leader):

:strip_icc()/pic1065263.png)

This is how it looked on the table:

:strip_icc()/pic6695140.jpg)

(These images courtesy of BGG because for some reason I can’t find my copy and am now worried that it’s lost , or worst, accidentally sold in one of my purges.)

Anyway, for the first few decades after modern wargaming began with the introduction of Tactics in 1954, the hobby was tiny, living on a shoestring, and catering to maybe a couple of tens of thousands of enthusiasts. Production budgets were very small, so two- or three-colour offset printing was the only affordable option. Box art tended to be spare, though graphic artists like Randall Reed and (especially) Rodger B. MacGowan produced some beautiful work for early wargame powerhouses SPI, Avalon Hill, and GDW. And at least Avalon Hill used mounted map-boards.

The principles of wargame graphic design inside the box were codified in the late 1960’s by Redmond Simonsen when he was basically a one-man graphic-design show at SPI. SPI was even poorer than Avalon Hill when it began, so SPI’s maps were never mounted, and Simonsen’s philosophy ran as follows: (a) keep costs down; (b) function over form whenever possible; and (c) keep costs down. SPI couldn’t even afford artists for its box covers at first, so they relied heavily on stock photographs when they had art on the cover at all. They also used lots of what we would today call Wingding iconography.

This is not to say that all wargames before 1990 were ugly inside and out–far from it. But old-school grognards grew up developing mostly low expectations for physical beauty in their games.

The games themselves were dominated by hex-and-counter move-and-fight dice-driven combat I-go-You-go mechanics again codified during the first golden age. Any divergence from that was treated with (at best) skepticism and (at worst) disgust. I mean, the introduction of morale checks in 1977’s Squad Leader, despite having been around in miniatures wargaming for decades, was considered a HUGE (and somewhat daring) innovation at the time. And Up Front? Pfft, a card game about tactical WW2 combat? Hard pass. (P.S.: Copies sell today for $200 and up.)(P.P.S.: It was way ahead of its time.)

I bring this all up just to explain how much of a game-changer GMT was when it came on the scene in 1990 as the first golden age of wargaming was coming to an end. Now, I have my problems with GMT’s corporate philosophy, but there’s no denying their influence–not just on wargaming but modern Tabletop as a whole. They basically pioneered crowdfunding with their P500 pre-ordering program, which ensured a paying audience for their entire line.

Furthermore, from the start GMT raised the bar for production values in wargames back to where they had been in the relatively lush 1970’s at Avalon Hill. Initially their box-covers adhered to the traditional style: Combat Commander and Command & Colors wouldn’t have looked out-of-place on a mid-70’s gamer’s shelf (although the type of cardboard GMT used for the box was both shinier and sturdier). And it’s no secret that Twilight Struggle’s cover art is downright ugly (I’m sorry, it’s true).

But soon GMT began to include mounted boards in all their games (or sold them as upgrades to those willing to pay). They used higher-quality stock for their counters which made them much easier to punch out (no more clipping off messy corners) and finally broke away from the NATO symbology which had been baked into counter design (even for games set in ancient and mediaeval times!) since the late 60s. And with games like 2006’s Command & Colors: Ancients GMT made woodblock components cool again, whereas up until then only Columbia Games’ Napoleonic-era and WW2 games made use of them.

Furthermore, from the start GMT was not afraid to publish games on topics far off the beaten consim track. 2007’s Conquest of Paradise was about Polynesian expansion during the first millennium, and Joel Toppen’s one-two punch of Navajo Wars and Comancheria shone the spotlight on two of North America’s most dynamic aboriginal nations. And to tell these stories, designers allowed themselves to be influenced by Euro-style mechanics.

Today, the GMT ‘brand’ announces itself on the cover with a reproduction of a beautiful piece of period art, and on the inside with high-concept graphics with gameplay to match.

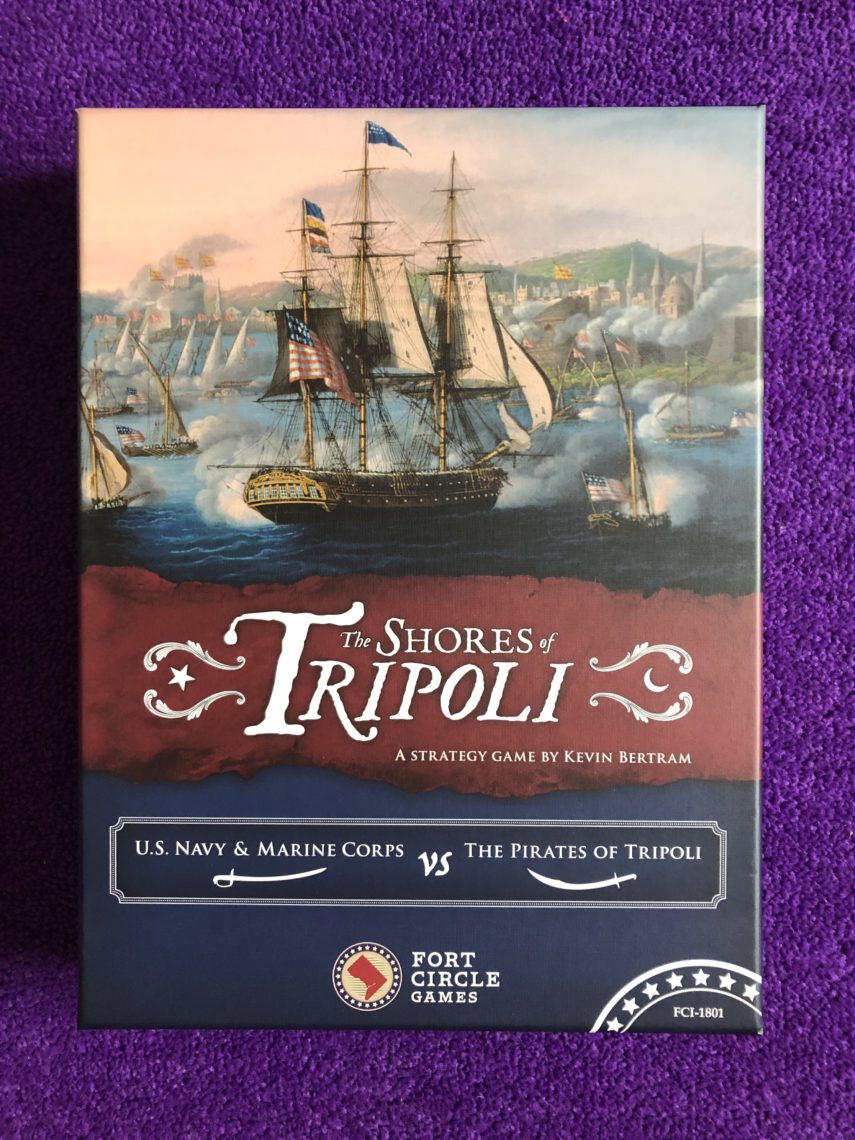

Which brings me back–finally!–to The Shores of Tripoli, by first-time designer Kevin Bertram and published by fledgling Fort Circle Games. You have to look pretty closely to realize that it is in fact, not a GMT game. Which is not a criticism–I’ll bet that’s the effect Fort Circle was aiming for. After all, if you’re new to the publishing game, you want to reassure buyers that they’re getting a quality product, and GMT is the standard.

(Sidebar: another recent design that followed this path was 2021’s Judean Hammer from Catastrophe Games. But I’m saving a writeup of this for closer to Hannukah for obvious reasons #grin.)

The box art of Shores of Tripoli appears to be a period painting of American frigates at sea, and the rule books are replete with reproductions of contemporary portraits, landscapes, and battle scenes. The first thing that greets you when you lift the sturdy box lid is a letter dated May 21, 1801 from Thomas Jefferson to the Pasha of Tripoli, Yusuf Qaramanli. It’s printed on glossy paper with old-timey-but-readable font and in it Old Tom swears up and down he’s only got peace on his mind, so pay no attention to that squadron of ships he’s sent over into the Mediterranean: they’re only there to safeguard American commerce.

A familiar story–and we’ll come back to it.

The rest of the physical components–mounted map with muted colour palette, wooden bits, cards on high-quality cardstock with more tasteful artwork–adhere to those GMT standards. There are even two booklets: one for rules and the other for historical and designer notes. Just like a GMT game!

All right all right enough with the GMT already. Where’s the beef?

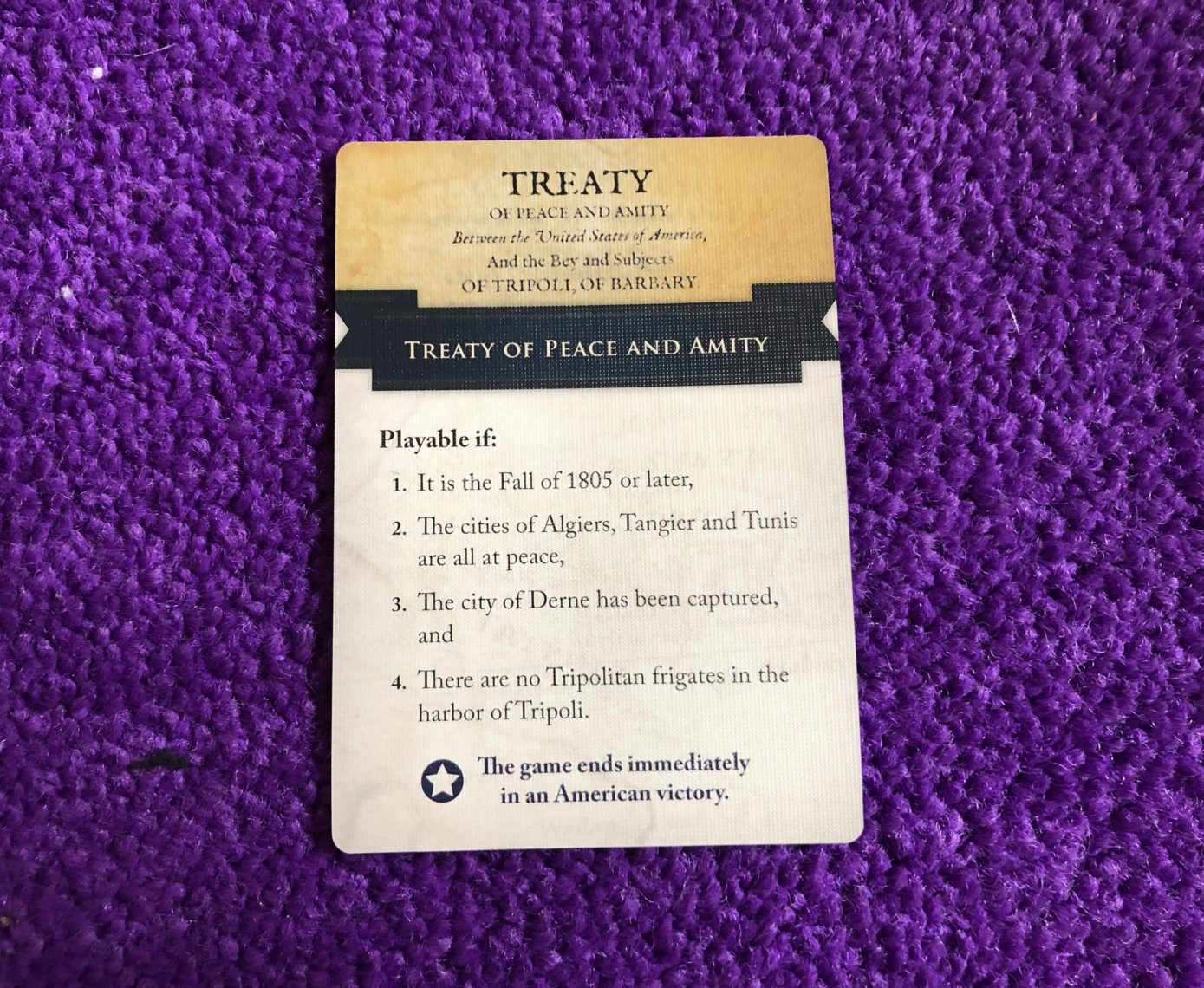

Shores of Tripoli plays out over at most six rounds each representing one year. The US is aiming either to impose a favourable peace treaty or conquer Tripoli and do some early 19th-century regime change. It starts with three frigates in Gibraltar (others arrive as reinforcements). ‘Murica also starts with 12 gold–GOLD!–which serves as one path to victory for the Pasha if she can steal it all via Pirate Raids.

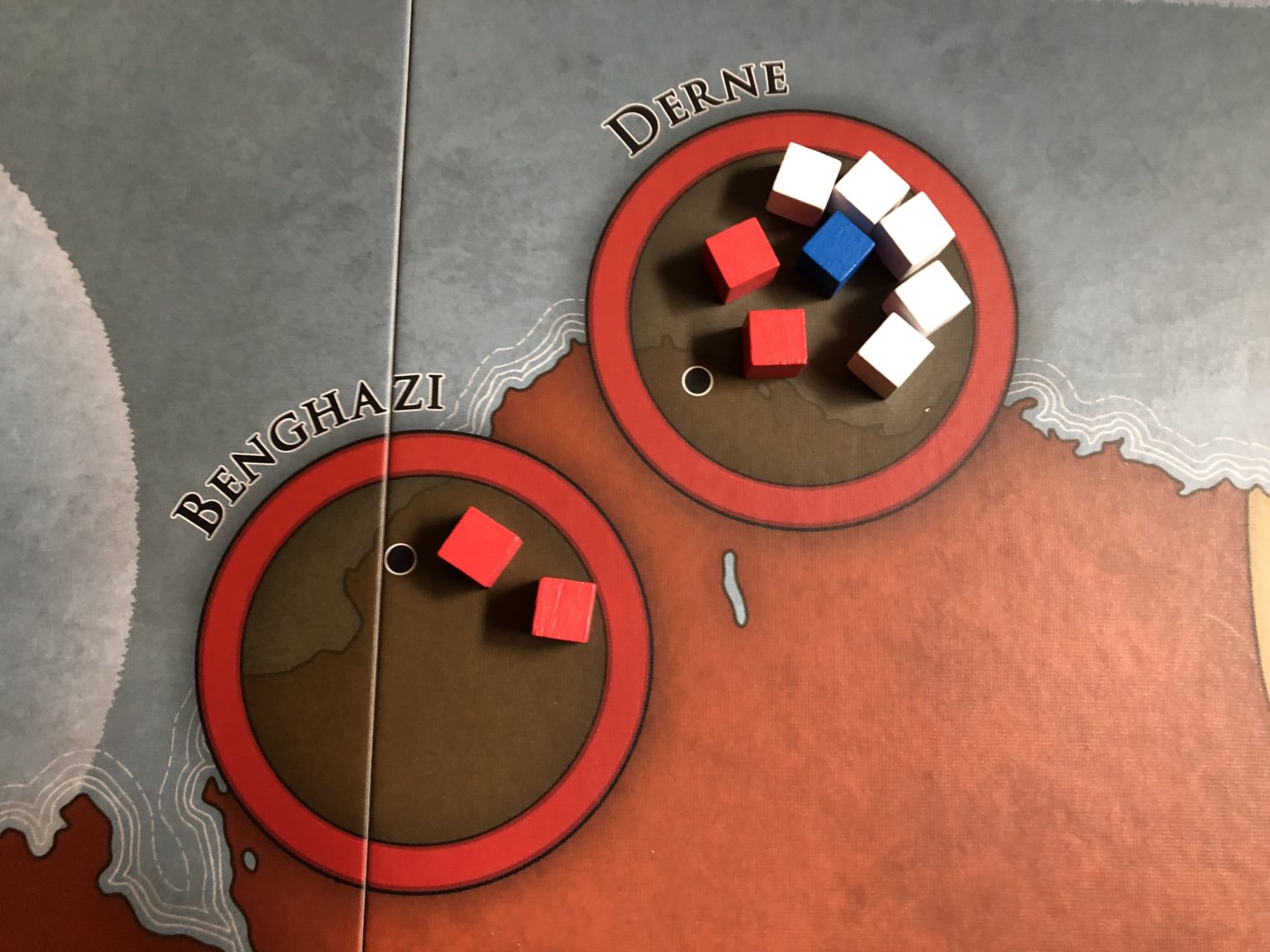

Meanwhile, the Tripolitan player has four corsairs (weaker than frigates) in Tripoli and two in Gibraltar which are mysteriously immune from attack (the rules explain it’s a neutral British port but it’s coloured blue like all the other American spaces–confusing). The Pasha also has some boots on the ground in Tripolitania acting as meat-shields for Tripoli. I already mentioned the first path to victory above. The second is to sink four US frigates, and the third is to eliminate all US infantry in their push for Tripoli.

Each year starts with both sides getting any reinforcements/replacements and then drawing six cards into hand up to a limit of eight. Both sides draw and use cards from their own unique decks, with some starting the game on the table ready to be played. Players then alternate playing cards starting with the US until each has played four, after which a new year begins.

This wouldn’t be a GMT-style Card-Driven-Game without multiple-use cards, and Shores of Tripoli follows suit here. Cards can be played for their event (leaving the game if one-use; going to the discard pile to possibly reappear later otherwise), or discarded to either build new ships or to move (US) or raid (Tripolitan). No passing is allowed, so you’ll always be using four cards per year–but cards that start on the table don’t count toward hand size, giving each side some flexibility.

Combat is a dice-chucking affair, whether naval, ground, or naval bombardment. Naval combat lasts for one round only; ground combat repeats until one side is eliminated. Corsairs, gunboats, and ground units can take one hit and then go back to the supply where they can be rebuilt. Frigates can take two hits but after the first they retreat from battle to return the following year as replacements. Only by hitting them twice in the same combat round can the Tripolitan player sink them toward their goal of four. There are also cards which can be played during battles to roll additional dice or modify the results.

That–plus the fact that the rules are ten pages of well-spaced and illustrated text–should give you enough of an idea of the level of difficulty of play. Shores of Tripoli isn’t aiming to be a simulation–which, given the scale of this particular conflict, is probably the correct choice. Instead, it’s trying to put players into the strategic driver’s seat(s) and tell a story. Which it does, very well.

The US player spends the first few turns building her fleet, neutralizing Tripolitain allies, getting things set up in Egypt for the final land push to Tripoli, and trying not to lose all her gold by blockading the port of Tripoli and investing in gunboats. The Tripolitan, on the other hand, wants to raid, raid, raid to try to empty out the US Treasury and, failing that, to time the activation of her alliances and reinforcements for maximum effect if the US goes for an invasion.

And that’s basically that. Shores of Tripoli isn’t particularly deep. I find that the victory path you shoot for very much depends on the cards you draw on the first two or three turns, and once locked in it’s not easy to change course. But to be fair, the game doesn’t have wild ambitions to be other than it is. It does what it sets out to do: shine a spotlight on a little-known corner of early American history with a well-balanced game (no surprise given the huge list of playtesters listed) which is a fine introduction to CDG’s, accessible to new players, and a fun little frill for grognards,

Overall, the rules are remarkably well-done for a small outfit–I can’t think of a single ambiguity or hole. The components are top-notch. There’s even a surprisingly-challenging and variable solo experience–though I don’t understand why the solo versions of the event cards weren’t printed right on them instead of forcing the player back to the rules. There’s plenty of space on most of them.

Which brings me to one carp–not a big one, not a dealbreaker, but one that bugged me nonetheless. Maybe Fort Circle wanted to avoid the mistake committed by many publishers of cluttering up the board and cards with charts or too many flashy-but-irrelevant illustrations. If so, I do applaud their spare approach; the overall effect of the muted but well-contrasting tones is lovely. But many opportunities were wasted to add information to the board and cards which would have reduced the number of times I had to refer back to the rulebook, which broke up flow and immersion. And because there is so much empty space, things like opening setup printed on the board spaces, combat reminders, and even ground movement lines between Alexandria and Tripoli would have made life that much easier for players trying to learn and play the game.

This is where GMT’s experience–and resources–come in. They’ve been to so many rodeos, heck they’ve built their own rodeo; they’ve learned how much the design of the GUI of a game can affect players’ experience of a game.

Another missed opportunity lies in the historical notes, which do a decent enough job of telling the story of the campaign but fail to put it in a broader perspective in terms of what it foretold of American policy. To me anyway the success of the Tripolitanian Campaign served as a proof-of-concept to American businesses that it was not only possible but necessary to use the levers of foreign and military policy to serve their own interests. The road that began in Tripolitania wound through Hawaii, Central and South America, and ultimately spanned the planet. I think this would have been worth mentioning.

All that aside, Shores of Tripoli is clearly a labour of love, and a triumph for designer Kevin Bertram. I look forward to seeing his upcoming work and Fort Circle’s releases in general.

Thanks to Fort Circle for providing a copy of Shores of Tripoli for this article.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!