Only a few tabletop games define and embody a genre; El Grande is one of them. All modern area-majority games trace their lineage back to it. Without El Grande there would be no Blood Rage, or Root, or Twilight Struggle. Or maybe they would have all happened anyway–poetic licence and all that–but there’s no denying that EG is OG. It came out in 1995, the same year as Catan.

But while Catan’s Klaus Teuber spent most of the rest of his illustrious career spinning variations on that winning formula, El Grande’s main designer, Wolfgang Kramer, has gone on to multiple successes with different designs, including the Mask Trilogy, Colosseum, and recently 2020’s Renature. All of those games were collaborations; Kramer evidently enjoys (and benefits from) having someone to bounce ideas off of.

In El Grande’s case, Kramer’s design partner was Richard Ulrich, with whom he also created another first-gen classic The Princes of Florence in 2000. Ulrich hasn’t been very active over the last couple of decades, with only a few credits to his name, mainly kids games and El Grande expansions.

So anyway, the reason I want to ring the bells for El Grande is that I played it last week for the first time in over a decade and boy, was I more than pleasantly surprised by how well it stood up. It’s not like I had been avoiding playing it for all this time for any reason. More like, “Those games were amazing for their time, but hasn’t game design moved on since then?”

Turns out, not so much. Or rather, it was a reminder that, as in all art forms, tabletop design is about knowing when not to add more.

El Grande is a game build around threes. The game is split into three “eras” of three turns each, after which there is a scoring round, during which the players finishing in the top three in each province (in terms of cubes placed) earn a certain amount of VP’s.

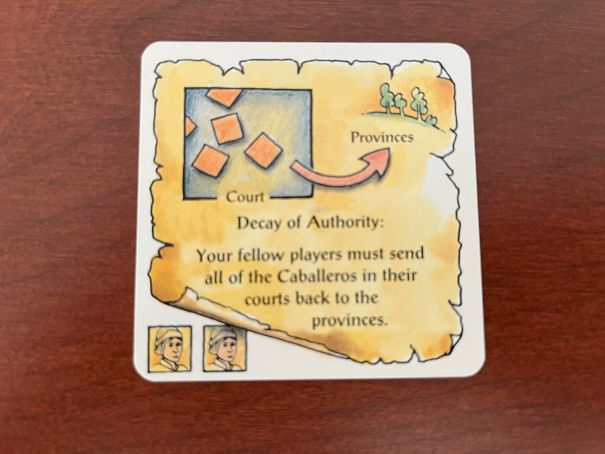

Those cube-dudes (caballeros in the game’s parlance, more about that later) are placed and moved around the map of Spain during the non-scoring rounds. Each player starts the game with a deck of cards numbered 1 through 13; the number determines “initiative order” for the following round. The higher the number, the sooner you’ll act, but the fewer caballeros you’ll be guaranteed to place. Going earlier matters because every round five action cards will be up for grabs, each of which has both a bespoke action which you may take (or not, your choice) as well as giving you the right to add more cubes to the board (or the Castillo, about which see below) as well. This second cohort of cubes must be placed in provinces adjacent (but not in) the province wherein the huge King pawn is resting his huge ass for the moment.

The Castillo is an actual tower on the map, into which cubes get tossed as part of that action-drafting. It scores like a province at the beginning of scoring rounds, but more importantly once it’s been scored each player gets to take their Castillo cubes and add them en masse into one province before the rest of the scoring. This selection happens simultaneously and secretly using cute little dials, so depending on the situation a region you thought was “solid” turns out to be “not so solid” (apologies to Adelai Niska).

I’m not going to go more into the weeds about gameplay or strategy–the game’s been out for almost 30 years, you can find plenty of articles on BGG. What I want to talk about is why you’d want to play El Grande today, in 2023. What does it have to offer?

What El Grande reminds me is that you don’t need point salads and mechanical tiramisu to provide gameplay depth, or replayability. Each game is different because the starting positions and available actions are always randomized. Certain actions are super-valuable if they come up early enough in the game and are basically worthless later, and vice versa. The King’s starting location is also random, and it’s vital, not only because it determines where action-cubes can be placed but also because the province he sits in is “locked down”: no cubes can be added or taken away for any reason. Moving the King is a great way to guarantee a victory in a province–or (by moving it away) opening up a rival’s province for conquest.

For a ruleset which seems simple by today’s standards (but which was brain-melty in 1995) the strategic and tactical questions are numerous. Which card do you play to insert yourself in turn order? Which action should you pick when it’s your turn? When should you choose the King-moving action? How many cubes should you toss into the Castillo? Can you remember how many cubes you’ve tossed in there?

This last question came up in my game last week because a couple of my gaming group are real perfect-information strategists, but all the side chatter and socializing kept distracting them from keeping track of even their own Castillo contributions. Which I loved–and hypothesized it was put in as a feature and not a bug, a remnant of a time when “games” meant “socializing”. It’s the type of mechanic you rarely see nowadays, this kind of blind fire-and-forget bidding.

The game works with three and is better with four, but really shines with five in my eyes. This ain’t no multiplayer-soltaire, moonpie. The more crowded the board is, the more difficult it is to jostle into the top three in any province, and the less you want to cop out and go last in turn order (as you occasionally must do) because you’ll be stuck with the action no one wanted (you can still place cubes, though).

Of course like all German games of the era the theme is totally ahistoric and has nothing to do with the mechanics–but I forgive it that sin. At least it’s set in Europe and not some sanitized colony.

I got rid of my own copy of El Grande many years ago, and playing it again almost made me want to reacquire it, even if game design has evolved since 1995, and my standard of thematic integration has risen. But truth be told, it’s not a game I need in my collection; I’m happy my friend has a copy, and I’ll play it once and a while happily–even more than once a decade, given the option. If you’re looking for something more recent that scratches the same itch there’s 2015’s The King Is Dead or last year’s First Empires. But if you get a chance, El Grande is still worth your time–and that’s more than I can say for some recent AAA games.

Thanks for revisiting this foundational classic, David. I always appreciate your long-view perspective and sincere reactions.