I, Alice Connor, once ruined a game of Kill Doctor Lucky by entirely forgetting to explain the spite tokens. Kill Doctor Lucky is essentially Reverse Clue, where you’re trying to kill the guy somewhere in his mansion in a spot no one can see you. Each failed attempt at killing the eponymous Dr. Lucky, whether with the assist of weapons on cards or with your bare hands nets you a spite token, charming red wood discs. And those discs add up! They’re very valuable because they can be used to stop other players’ murder attempts. But they’re also valuable because they add to your own murder attempts every time. For example, if I tried to kill Dr. Lucky with poison for, say, 3 points, the other players would need to try to stop me with three points of their own combined cards or spite tokens. Well and good, unless I’ve tried and failed to kill him 10 times before—then, I’m attempting murder with 3 points of poison and 10 points of unbridled spite. The game gets increasingly tense as all players grow more and more spiteful and vast handfuls of spite get shoved across the table to keep other people from winning. Unless you completely forget to share the spite rule. Sigh.

I’ve invited DWP staff to share their own moments of rule-forgetting in this week’s “amuse bouche” article, an informal series answering short questions.

David W.:

About ten or so years ago at my club’s usual Thursday FLGS game night, I pulled the first edition of the just-released 51st State off the New Releases shelf and said, “Huh!? This looks interesting. Let’s give it a whirl.” It looked like a tableau-builder a la Race For the Galaxy with a post-apocalyptic twist. I was used to teaching games out of the box, there were only a few pages of rules to this game, I figured how hard could it be?

Ah, but I’d never played a game by Ignacy Trzewiczek before. By his own admission, Ignacy’s games are eternal works-in-progress and his rules are written and organized very idiosyncratically. If “organized” can even be used.

It’s all a bit of a blur now with the passage of time, but I remember we restarted the game at least twice because some important rules were unusual and confusing (drafting cards in the Lookout Phase; how to use Range tokens; the difference between Incorporation and Development). Other important rules were tucked away in unexpected places, and others were only implied instead of, you know, in the rules. Could you or couldn’t you use other players’ locations? How many times could you use them? How did attacking work?

I was very frustrated and felt awful for the other players I’d dragged into playing this mess. But by the end of the night I was hooked—it was clearly a heavily-thematic and original game where each faction played differently and you could smell the diesel oil. The Master Set edition which came out some years later cleaned up almost all the messy bits and Ignacy went on to refine the ideas from 51st State in the more-successful Imperial Settlers franchise.

Bailey D.:

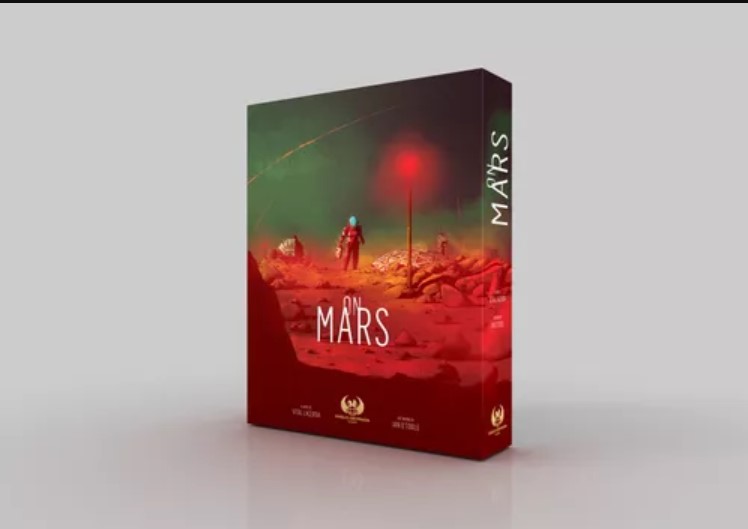

So, here’s the thing. I’m a studied rules teacher. Truly. I spend a lot of time preparing to teach others games. Once, I spent a week prepping to teach my game group On Mars by playing it three-handed, four times, reading the rules afterwards every time, in addition to many rules teach videos before my first “solo” play.

However, I do not put in that much effort when I’m worried about teaching myself a game. Enter every single game of Root I’ve ever played.

Take probably the most egregious example of this phenomenon: My failed Ottersman Empire run last time I played the Riverfolk Company. For those that don’t know, every faction in Root plays differently from one another, so it’s a rules nightmare. But I somehow miss the most obvious of rules, the ones printed on the player mat.

The Riverfolk Company’s main “thing” is that they can sell their cards to other players in exchange for the other player’s meeples. These meeples can then be spent to do additional actions on their turn. So, spend the meeples, do more things. However, if you do not use those meeples for more actions, you can gain victory points!! Woohoo!!

Here’s where I messed up: When the Riverfolk Company loses one of their buildings out on the board, then they lose their unspent meeples. I was removing spent and unspent meeples, even though the rule was printed twice on the player mat. Suffice to say, I spiraled and did nothing in that game.

Reeve L.:

As games get more complex the propensity to forget rules when teaching friends increases. In most cases forgetting a minor rule here or there does not fundamentally alter the mechanics of the game, but rather changes viable playstyles and strategies. Sometimes, a rule can be forgotten to change the game so much that it becomes unplayable. I once forgot while playing Viticulture that players do not retrieve workers between the Summer and Winter seasons; players must carefully choose when to place their workers, knowing they’re stuck until the following Summer. Taking them back mid-year rapidly led to a playthrough with free-flowing money, no tough decisions on how to use workers, and a completed game in under 45 minutes. It went from a thoughtful strategy game about wine to an impulse-driven, fast-action game about making grape juice.

Gamers, we all know the stress of teaching a new game to your group. Sometimes it’s hilarious to look back on a missed rule—Alice recalled in a recent Table Talk podcast teaching Jericho and allowing way, way too many cards to be tossed into the scoring pile—but if the other players at the table are too harsh, missing a rule can be painful. This is Taylor G writing here imploring us all, regular and occasional gamers alike to remember your own tough teaching experiences when learning from someone else. Teaching a game is a whole skill on its own, separate from the actual play. The person teaching wants you to have a great time. They didn’t leave out that rule until the middle of the game on purpose. If you know the game well, but you’re not the teacher, save your comments and corrections until the end of the teach. If a rule gets missed and it messes up your game, remember it was a game, after all. The reason we come to the table isn’t perfection, it’s the people. Keep the good stuff in mind and hold a gracious space for your brave game teacher.

[…] though, remember that time we talked about teaching rules wrong? The first (and maybe second and third?) time I taught Jericho I taught it wrong. Embarrassing. We […]