About two months ago I asked the question: “are there topics which are inappropriate to turn into games?” (TL;DR answer: “Mmmmmaybe.”) Right around that time I saw a posting on BGG about a game called This Guilty Land, which purported to be about the political struggle over slavery in the United States in the decades leading up to the American Civil War (ACW).

There is no way I can cover even the barest bit of the issue of slavery’s role in shaping Western culture. Suffice to say that I believe that (a) it is a very painful legacy that definitely lives on today; (b) many have yet to come to terms with it–or are in denial that there is anything to come to terms with; and (c) any attempt to gamify the story is fraught with danger.

I want to quickly deal with the game itself as a game and then move on to talking about how the game navigates the dangerous terrain of its theme.

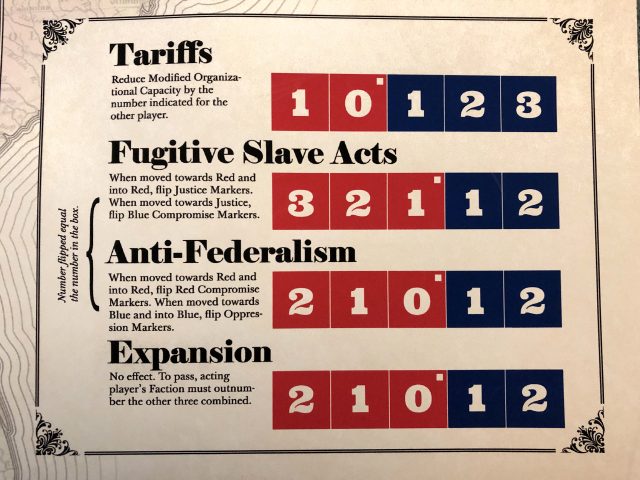

This Guilty Land is a two-player game that plays out on an abstracted political map of the United States. One player represents the forces of Oppression which are trying to maintain slavery, the other the forces of Justice working towards emancipation. Gameplay is similar to many GMT CDG’s (card-driven games) but there are refreshing differences. Players have no “hands” per se; instead, they draft multi-use cards from a common display, either playing them directly or putting them into their (generally face-up) Reserves. These cards are used to sway public opinion (which in turn shifts electoral support), organize (which increases your ability to act at the expense of some public support), and try to pass laws which will benefit you. Every card you play also costs Political Will, which you generally earn through your opponent’s actions on their turn.

There are many ways to earn victory points, mainly through the ongoing effects of passing laws favorable to your cause. This means it is absolutely necessary to build and maintain support in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. This in turn requires constantly striving to take and keep the initiative to force your opponent to react to your moves instead of vice versa. Timing is crucial, and since most cards are face up your opponent knows pretty much what you know, so distraction and bluff are key skills. But one thing the game’s rules make clear is that, whatever the political outcome, the Civil War is going to happen one way or another. This may not please players who like to play these games to change history, but as you will see below the designer was not interested in creating that type of game.

The game’s components are also reminiscent of GMT: unmounted map, flimsy cardstock. The rulebook is excellent, however, with no rules issues, and (again, like GMT) there is a second Playbook which has a full playthrough, commentary on the cards, and (most importantly for our discussion below) an in-depth interview with the designer, Tom Russell.

I would say that if you enjoy politically-themed games like Twilight Struggle or 1960: Making of a President and are at all interested in this era, then This Guilty Land is a worthy addition to your library.

But to some people, the slavery theme is enough to turn them away from This Guilty Land, full stop. The idea of “playing” with slavery is distasteful to the extreme for them. How could one, in good conscience, enjoy a game about the suffering and misery of millions? Why would someone want to embody–possible even sympathize with–the slaveholder mentality, for the sake of a couple of hours of tabletop enjoyment?

These points give me pause. I play historical games for their simulation value, as a means of understanding the past, because I have that clichéd belief that “those who are ignorant of history are doomed to repeat it”. The events of the last couple of years bear that out, I believe. I definitely seek enjoyment from consim games–but my love of history is what draws me to them, the hope that I will come away understanding more.

Yet I cannot dismiss the arguments against games that touch on slavery out of hand. If I felt that a game was simply sensationalizing the issue of slavery, or using it as a pasted-on theme, or coming at it with poor and biased research, then I would definitely not want to play it, let alone buy it. The task at hand, then, is to investigate designer Tom Russell’s approach and decide whether This Guilty Land is a game I can roll with, or not.

At first inspection, the game’s box cover could definitely raise eyebrows. Front and centre is a photograph of what one assumes is a slave, sitting turned away from the camera but head in profile, left arm awkwardly akimbo, revealing a back positively covered in thick ridges of skin one can only assume are the scars of innumerable lashings. Sensational much?

Turn the box over, though, and you will find out this photo is of an escaped slave named Gordon who enlisted in the Union Army, and that the photo was wide circulated as an anti-slavery message.

Also prominent on the back cover are quotes from abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and John Brown, and a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. which has seen much play on Facebook recently (on my feed, anyway) regarding the danger that moderate whites pose to the civil rights movement by their tendencies to favour accommodation and compromise over direct action.

So, while the shocking imagery of the cover may raise some red flags, the message of the box art and text paints a more complicated picture.

In the interview with Russell, he makes no bones about his opinion of his role in telling the story of slavery in America:

[I]t’s about the legislative underpinnings and the tendencies in the public discourse that allowed slavery to continue — and not about the lived experience of slavery. Because I don’t feel that story is my story to tell. You know, I’m a white, straight, middle class man who makes board games for a living. I’m not marginalized or oppressed in any way. So I’m not going to tell that story. My voice isn’t useful there, if that makes sense. So this is very specifically about the kind of systematic structure that allows oppression to continue as it were.

To me this makes Russell’s aspirations plain: his game is about slavery at the systemic level, not trying to appropriate the struggles and suffering on the ground.

Later in the interview, Russell deals with the issue of “roleplaying” in the context of his game:

A lot of historical games, they look at it from the point of view of, “I’m putting you in the shoes of these historical actors. I’m going to give you their goals, and let you view the world through their eyes.” And not to put too fine a point on it, but I have no interest in viewing the world through the eyes of people who owned other people. Of people who torture, enslave, and rape, and murder other people. I don’t need to understand their viewpoint. I don’t want to elicit an understand of their viewpoint.

For me, this puts to rest any accusation that playing This Guilty Land is about building empathy for slave-owning.

Which is not to say that playing the game is supposed to be a feel-good experience. As Russell says at the beginning of the rules, “Some players will be uncomfortable with the idea of playing Oppression. This discomfort is intentional.”

There is much more in the interview, and I urge anyone who is interested to listen to the whole thing here (it’s about 90 minutes long–the section on This Guilty Land begins at about the 9 minute mark).

All in all, I believe that This Guilty Land is an impressive indie design that is just as good as any GMT CDG, and which I believe enables players to emerge with a better understanding of the systemic roots of slavery and the attempt to break its stranglehold on the American economy and psyche. Unfortunately, the latter struggle is still not over.

(The Daily Worker Placement thanks publisher Hollandspiele for a review copy of This Guilty Land.)

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!