Why do designers and publishers retool their tabletop games as card games? (Or dice games, sure, but my focus this week will be on cards even though almost everything I have to say applies to dice versions as well.)

The obvious answer is: money, duh. If suckers fans enjoy Game X, it is likely many of them will be willing to fork out the green stuff for something similar YET different enough to justify the purchase.

Less cynically, card versions are also a tempting challenge for designers: can they distill the essence of the original game into a smaller package using only cards? Limitations spur creativity.

But, realistically, how often do these cardaptations (yes, I like the sound of that #portmanteau) ever reach the heights, let alone exceed, the experience of the original game? Let’s do a bit of digging and find out.

* * *

The grandpappy of modern tabletop, 1995’s (Settlers of) Catan, spawned a card-based version very quickly. Catan Card Game (as it’s known now) came out in 1996 and naturally sold well, for all those looking for a portable version of their new bff. Designer Klaus Teuber adapted Catan for cardplay by making it a two-player-only game. Each player had their own tableau-grid of (rectangular) resource-producing cards with roads and buildings set in between. Most of the mechanics and paths to victory from Catan remained the same, but there was an additional die that introduced other kinds of events.

The grandpappy of modern tabletop, 1995’s (Settlers of) Catan, spawned a card-based version very quickly. Catan Card Game (as it’s known now) came out in 1996 and naturally sold well, for all those looking for a portable version of their new bff. Designer Klaus Teuber adapted Catan for cardplay by making it a two-player-only game. Each player had their own tableau-grid of (rectangular) resource-producing cards with roads and buildings set in between. Most of the mechanics and paths to victory from Catan remained the same, but there was an additional die that introduced other kinds of events.

Catan Card Game never attracted the same level of following–probably in part because as a card game it lacks the iconic hex-based board and wooden bits that drew people to Catan in the first place. Today it’s rated 6.8 on BGG, versus Catan at 7.2. For Catan’s 15th anniversary in 2010, Catan Card Game was reissued with some significant tweaks and, ultimately, many expansions, as Rivals for Catan. This version has proved quite a bit more popular, rating almost exactly a 7.0.

The next big cardaptation was 2004’s San Juan, descended from Andreas Seyfarth’s 2002 blockbuster Puerto Rico (which I wrote about back in 2017). In this case, the cardaptation was good (and different) enough to win fans all on its own. Seyfarth kept the role selection and production mechanics that made PR so iconic–how could he not?–but made the game revolve around hand management. Cards themselves became the currency which had to be spent from hand to purchase buildings, and were also used (drawn from the deck face down) as resources.

San Juan is an excellent game with its own iOS adaptation and, though it would be hard to beat PR’s 8.0 rating on BGG, it sits just outside the top 200 with an average 7.6 rating, a great rating all on its own. Fun fact: 2007’s Race for the Galaxy began life as Tom Lehmann’s attempt at a PR cardaptation, but when Seyfarth said he was working on his own version, Lehmann reskinned it and spawned his own very successful franchise.

* * *

Here is a chart listing some of the most successful cardaptations out there, with their BGG rank compared to their tabletop parent:

| Base Game | BGG Rating (as of Nov. 2, 2018) | Cardaptation | BGG Rating (as of Nov. 2, 2018) |

| Castles of Burgundy | 8.1 | Castles of Burgundy: TCG | 7.1 |

| Puerto Rico | 8 | San Juan (2nd edition) | 7.6 |

| Power Grid | 7.9 | Power Grid: TCG | 6.9 |

| Dominant Species | 7.8 | Dominant Species: TCG | 6 |

| Space Hulk | 7.5 | Space Hulk: Death Angel | 7 |

| Ticket to Ride | 7.5 | Ticket to Ride: TCG | 6.2 |

| Samurai | 7.4 | Samurai: TCG | 6.3 |

| Catan | 7.2 | Rivals for Catan | 7 |

| Broom Service | 7.2 | Broom Service: TCG | 6.2 |

| Alhambra | 7 | Alhambra: TCG | 6.5 |

| Dark Souls: The Board Game | 6.7 | Dark Souls: TCG | 7.2 |

| Clue | 5.7 | Clue: TCG | 5.8 |

| Monopoly | 4.4 | Monopoly Deal Card Game | 6.3 |

And, for you quant-heads out there, a scatterplot of the above:

As you can see, in only three cases (Monopoly, Clue–barely, and Dark Souls) was the cardaptation considered an improvement on the original–and two of those are ancient warhorses that could only be improved by an infusion of modern design technique.

So where, finally, does Carson City fit into all this?

* * *

Carson City (CC hereinafter) was released in 2009 and designed by Xavier Georges, whose main credits aside from CC are 2010’s Troyes and Ginkopolis from 2012, and various expansions and new editions of all three.

CC was a blending of three main mechanics: role selection to draft special abilities at the beginning of the round, worker placement to assign actions, and tile laying to build your Wild West town. Everything meshed together neatly and thematically, and I think it still stands out as a great design.

Georges was probably inspired by the 2015 Big Box treatment to revisit his creation and see what he could do with it. His choices are fascinating. CC:TCG is essentially one big card-drafting game, with bidding replacing worker placement as the “meat” of the game. The game is now split into two Eras of nine rounds each. In each round a certain number of terrain cards (depending on the number of players) and one character card (whose function replaces role selection from CC) are up for bidding. Players bid simultaneously using individual decks numbered from one to nine; each player’s cards are in a different suit, to help resolve ties. Highest bid gets first choice, followed by each of the other bids in order. The second-Era choices are generally higher-powered, so you need to set yourself up in the first half to cash in in the second–but be flexible enough to switch strategies if the cards you need don’t come up.

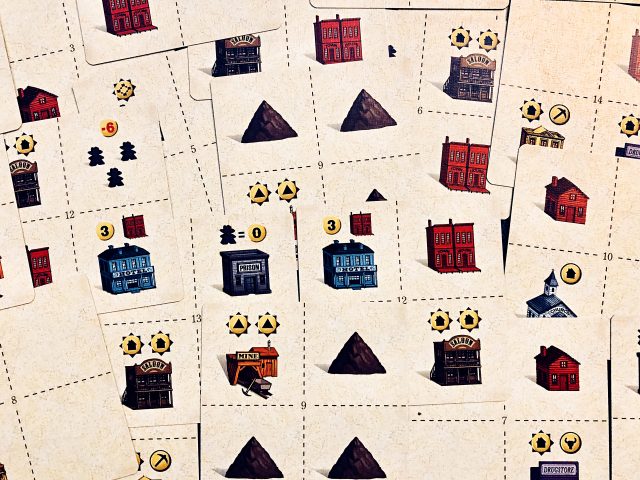

After bidding, players who won terrain cards must add them to their town. As in CC, there are many paths to victory. You can try to go heavy on mines, or ranches, or different town buildings, each of which scores differently. Sometimes adjacency matters, sometimes not. You can overlay terrain cards on top of each other (thereby upgrading certain kinds of buildings)–and in fact you generally will have to do so since your final town cannot be bigger than four cards high and four cards wide.

After bidding, players who won terrain cards must add them to their town. As in CC, there are many paths to victory. You can try to go heavy on mines, or ranches, or different town buildings, each of which scores differently. Sometimes adjacency matters, sometimes not. You can overlay terrain cards on top of each other (thereby upgrading certain kinds of buildings)–and in fact you generally will have to do so since your final town cannot be bigger than four cards high and four cards wide.

Character cards stay to the side of your town and have different powers. A couple are just worth victory points, but most of them are very useful–depending on what path to victory you have chosen.

CC:TCG must always be played by a minimum of four (to a maximum of six) players, which some might see as a disadvantage. For me the coolest part of the game is how simply Georges has incorporated bot play to take the place of missing players, which means solo and two-player play is not only a snap but extremely challenging–especially since you can tweak the challenge level of your artificial opponents so easily. It really is genius, and a real selling point.

My only complaints about the game are three and they’re minor. One is that the iconography on the tiles, rules, and player aids is a wee bit too small for my ancient eyes, but I’m sure you young’uns won’t have a problem. Second is the scoring, which some will find a bit cumbersome–it is practically Agricola-like–but I think it’s worth it. Third and most annoying is the insert, which is useless (as usual), so be prepared to toss it and bag your cards.

Overall as you can see, I’m kind of in love with this game, even without the cowboy meeples and gunfights. BGG seems to agree: CC:TCG rates a 7.1 versus CC’s 7.3, which makes it one of the more popular cardaptations, up there with San Juan, Dark Souls, and Castles of Burgundy: TCG. If you’ve never played the original, don’t let that stop you from trying this. And if you have, well, need I say more wink wink nudge nudge.

Congratulations to Xavier Georges for refusing to settle for mediocrity and instead embracing the challenge of the limitations of distilling everything down to a couple of hundred cards.

Now about those dice games…

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!