It’s been a few weeks since I last recommended an oldie but goodie, and last week’s British election had me thinking about a game I haven’t played in a while but which I think should be on your bucket list. It’s a six-hour game about German politics called…

Wait. Come back! Listen.

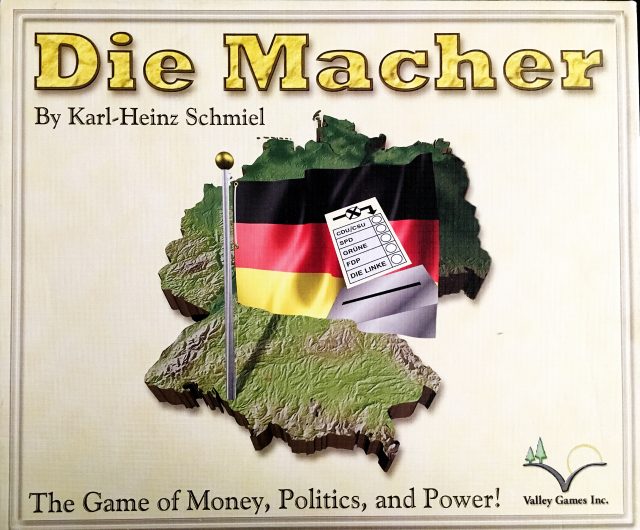

When BoardGameGeek was founded in January, 2000, do you know what the first game entered into the database was? This game. Die Macher, by Karl-Heinz Schmiel. He went on to design some other well-though-of games, like A la Carte and Saint Petersburg, but Die Macher was his magnum opus, and it was the first game on BGG.

How do I know that, you ask? Well, every game in the BGG database has a unique ID number based on when it was entered. It’s right in the URL for the game. For example, Flatline (which Nicole just wrote about) is the 216597th game to be entered–which is pretty mind-blowing all by itself.

But Die Macher’s ID is 1. That’s got to mean something in this crazy mixed-up world.

First released by Hans Im Gluck in 1984, it was out of print for a while and then republished by Alberta’s own Valley Games in 2006. Unfortunately, because Valley Games is no more, copies are again not easy to find. But I am here to tell you that if political games are up your alley, then it is worth finding a copy (or making a friend who has one). And I’m not alone; the game still sits at #148 on the all-time list after more than thirty years.

First released by Hans Im Gluck in 1984, it was out of print for a while and then republished by Alberta’s own Valley Games in 2006. Unfortunately, because Valley Games is no more, copies are again not easy to find. But I am here to tell you that if political games are up your alley, then it is worth finding a copy (or making a friend who has one). And I’m not alone; the game still sits at #148 on the all-time list after more than thirty years.

Macher literally means “maker”, but in German and Yiddish a macher is someone who makes things happen–a mover and/or shaker. In Die Macher between three and five players–though the game really should only be played with five–represent party leaders vying for seats in a series of seven state (ie, provincial) elections. At any given time there are four elections in play–the one which will be decided that round, plus the next three.

But although the lion’s share of points (and revenue) comes from seats won in elections, as party leader you are also tasked with growing your party membership and “brand”. Party Membership dues are an important revenue source. But most importantly, there are pretty hefty VP bonuses at the end of the game for how large your party is, its presence in the national media, and how well your policies match public opinion (which of course can be deftly manipulated by the proper application of the grün stuff).

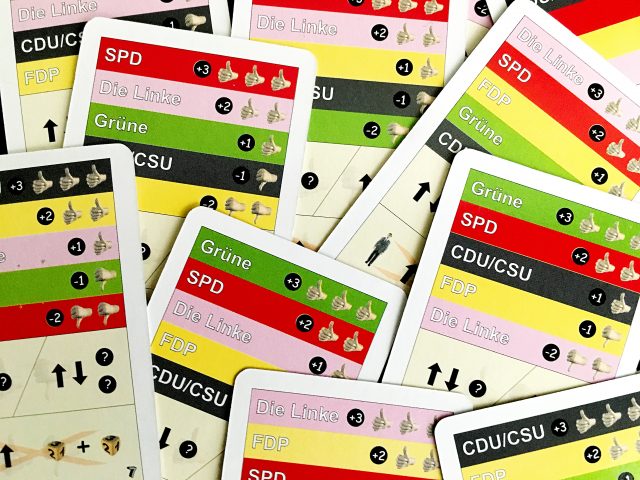

Public Opinion and Party Policy are represented by separate decks made up of cards showing support for or against seven broad categories: social security; wages; taxes; nuclear power; terrorism; GMO’s; and economic redevelopment. Each party begins the game with a randomly- generated platform of five cards. Each state in play gets Public Opinion cards indicating its stance–but the further away (in time) a state’s election is, the more of those cards are face-down. As a state’s election gets closer, those cards will flip over and players will know more about those voters’ preferences–which can make a big difference come Election Day.

Naturally, party platforms “evolve” as time progresses, to reflect mature reflection on the important issues of the day. (#Underwood2020)

Once the game is set up but before the first turn even begins there is  something called The Preliminary Phase where each player gets to secretly choose their starting setup from among various options involving Party popularity, membership, media presence, and even outright votes. This generates the essential asymmetry without which the game would lack balance and tension–and helps players catalyze their early-game strategies.

something called The Preliminary Phase where each player gets to secretly choose their starting setup from among various options involving Party popularity, membership, media presence, and even outright votes. This generates the essential asymmetry without which the game would lack balance and tension–and helps players catalyze their early-game strategies.

Each of the seven rounds starts with a secret bid for Start Player, which can have huge effects and is therefore an agonizing decision, especially late in the game (but also depends on how much money is out there, which is of course secret). Going first is great for most things but for winning elections you want to be last, take it from me.

The Platform Conference comes next, where players can choose to morph their Party’s policies to better reflect voter preference or align their Party more (or less) with another player, which has certain strategic implications (see below).

Following that is the Shadow Cabinet Phase, where players may choose to play one of their Shadow Cabinet cards to shake things up. Each player begins with an identical set of them, they are one-use-only, and they cost money to play–so deciding if and when to play them is yet another agonizing decision.

On top of that, playing certain Shadow Cabinet cards make that player available for Coalitions–which may or may not be a good thing. Coalitions can be a way for a player to ride the coattails of a stronger opponent to victory in an election–which can turn the tide in the overall game.

Next comes the Media Buy Phase. There are a limited number of these available, and the Starting Player gets first shot at them. Whoever controls the media in each State is immune to bad polls and gets to swap out a face-up Public Opinion Card in that State with one which helps their party (or hurts everyone else) the most.

Party Meetings come next–cubes which players buy and place in states with an eye to converting them into votes at some point. You can only buy four at a time, though, so a certain amount of forward budgetary planning is necessary.

The Opinion Polls Phase is next, in which players bid for the right to look at a face-down card which modifies voter opinion. It may or may not be of immediate help to your party–but it might be worth buying just to slag other folks. Or, you can toss it and increase your Party membership by a random amount. As the game goes on players tend to have more money, so the bidding for this can get ridonkulously high.

The Opinion Polls Phase is next, in which players bid for the right to look at a face-down card which modifies voter opinion. It may or may not be of immediate help to your party–but it might be worth buying just to slag other folks. Or, you can toss it and increase your Party membership by a random amount. As the game goes on players tend to have more money, so the bidding for this can get ridonkulously high.

Just before the Election is tallied, players get a chance to cash in Party Meeting cubes for votes. The more popular and “in sync” your party is, the more votes your Meetings will generate. Knowing when to take advantage of a surge in the polls ahead of time and when to hold off is a key skill.

FINALLY, the Election for the current state is resolved. Any remaining Meetings are converted into votes, and the Party or Parties with the most votes is the winner–with ties going to the Party (or Coalition member) who went last in turn order. The winner(s) get chances to place Media presence on the National level (worth points at game’s end) and add or alter National Public Opinion. Then each player gets to earn money according to the number of votes received and gain Party membership depending on how well their current platform matches National Public Opinion.

The current State board is wiped and (before Round 4) a new State is drawn and set up in its place. The next State in line becomes the Current State and the next Round begins with bidding for turn order.

I hope I haven’t gone into too much detail to scare you away–but I wanted to go into enough detail to illustrate how immersive and engrossing this game is. There is almost no downtime in Die Macher; every player is active in every phase and the decisions come fast and furiously. This is one of a handful of games (I think we all have some; Mage Knight is another for me) where hours can fly by and I do not feel it. Despite the complexity, despite the number of interlocking parts–or probably because of it–the game takes on a shape and narrative which is gripping and satisfying.

The biggest strategy challenge (in my mind) is managing your cashflow through the game. Go big in one State and you may win it–but end up too cash-poor to compete ever after, with disastrous consequences. To paraphrase what JFK once said, referring to his papa Joe’s rumoured “intervention” in the 1960 US election, you don’t want to buy one more vote than strictly necessary.

The biggest strategy challenge (in my mind) is managing your cashflow through the game. Go big in one State and you may win it–but end up too cash-poor to compete ever after, with disastrous consequences. To paraphrase what JFK once said, referring to his papa Joe’s rumoured “intervention” in the 1960 US election, you don’t want to buy one more vote than strictly necessary.

Die Macher’s design forces players to think ahead and adapt. There are sixteen States, worth between 20 and 80 seats, of which only seven are used in any given game. And since the order in which States appear is also random, with only four in play at a time, every game demands a different long-term and flexible strategy.

Not that the Valley Games edition (the version I own) is perfect. The rules are in Comic Sans font…which being a typographic snob I look down upon. The iconography on the Party Platform and Public Opinion Cards is cheesy and–more unforgivably–confusing and hard to read at times, which considering they are a major part of the game is a downer.

Not that the Valley Games edition (the version I own) is perfect. The rules are in Comic Sans font…which being a typographic snob I look down upon. The iconography on the Party Platform and Public Opinion Cards is cheesy and–more unforgivably–confusing and hard to read at times, which considering they are a major part of the game is a downer.

Some will find the fact that any party can espouse any platform to be annoying; others will point out (correctly) that the random order and appearance of the States (which is a huge replayability plus) is hardly realistic. To those people, I say “Bah!”

“Bah!” I say! Die Macher never pretends to be a sim. It is a game. If it were a TV show it would be “Yes, Prime Minister”, not “House of Cards”. But it is the boardgame equivalent of binge-watching an entire season. It takes commitment to learn and digest the rules, and it takes a considerable about of sitzfleisch to play. But I still have a scoresheet of a game I won five years ago up on my fridge–that’s how satisfying it is to win it is, and how important this game is to me.

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!