Let us sing the praises of Stefan Dorra.

Though not as high-profile or prolific as the other Germans who rose up the ranks in the 1990’s, Dorra has designed well-thought-out and elegant games for over twenty years, including Medina, Nyet, and Pergamon. Last year he came out with the well-received Valletta, which had a fresh take on deckbuilding.

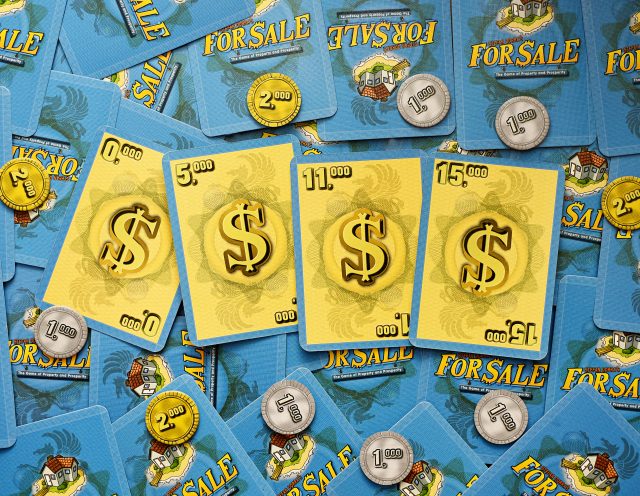

But it is 1997’s For Sale that I want to highlight and celebrate this week. It is the epitome of what we call “light filler”–which is meant as a very high compliment. For Sale is the perfect way to start or end an evening of gaming, or to cleanse the palate between heavier games. And, even better, it takes up very little space and is highly portable, regardless of which edition you find–particularly the 2008 Gryphon Games edition which is tuckbox-sized.

For Sale plays out in two acts. In the first, players bid on and draft property cards using their starting money. In the second, they bid on and draft cheques using the property cards they won in the first act. Whoever ends up with the most money wins. The game takes five minutes to teach, is language-independent, and scales well from three to six players. What more could you want?

Every round in the game presents a fresh set of interesting decisions. In the first half, properties are auctioned off in groups equal to the numbers of of players. You have to keep increasing your bid or pass and take the lowest-valued property remaining. There are thirty unique properties valued from one to thirty thousand dollars, from a cardboard box all the way to a space station; the card art in the North American edition finds the perfect balance between humour and realism. Your starting money is never supplemented by income, so you can’t get carried away with your bidding or you’ll be forced to take crummy properties for the rest of the first half.

Every round in the game presents a fresh set of interesting decisions. In the first half, properties are auctioned off in groups equal to the numbers of of players. You have to keep increasing your bid or pass and take the lowest-valued property remaining. There are thirty unique properties valued from one to thirty thousand dollars, from a cardboard box all the way to a space station; the card art in the North American edition finds the perfect balance between humour and realism. Your starting money is never supplemented by income, so you can’t get carried away with your bidding or you’ll be forced to take crummy properties for the rest of the first half.

If the optimal strategy were to end the first half with a hand of high-valued properties, the game would be okay but not stunning. The fascinating thing is that what you really want to go into the second half with is mainly high-valued properties but also with a couple of duds, for reasons I will explain shortly. This subtlety is what takes For Sale from okay to brilliant.

In Part Two, groups of cheques from a deck of thirty (two each of zero through fifteen thousand except none worth one thou) are dealt out, and you blind-bid for them simultaneously using the hand of property cards you won in Part One. The highest bid (and there will be no ties because all the properties are uniquely-valued) gets first choice from among the cheques; the second-highest bid gets second choice, and so on. If you have a perfect memory you will know who is holding which cards–particularly the highest-valued ones (30 down to about 25), so when the high-value cheques come out you can predict pretty well who will win and therefore what you should bid.

So what would you do in this situation: the cheques up for auction are 15, 13, 4, and 0. The highest remaining property out there is a 26 but you don’t have it and you don’t remember who does. The highest card you have is a 21, and then some in the mid-to-high teens. This is where having a couple of low-valued properties is useful–for sloughing off in situations like this where you doubt you can be the highest bid but you also don’t want to risk using up a decently-valued card and still coming in last or second-last.

So what would you do in this situation: the cheques up for auction are 15, 13, 4, and 0. The highest remaining property out there is a 26 but you don’t have it and you don’t remember who does. The highest card you have is a 21, and then some in the mid-to-high teens. This is where having a couple of low-valued properties is useful–for sloughing off in situations like this where you doubt you can be the highest bid but you also don’t want to risk using up a decently-valued card and still coming in last or second-last.

For Sale never outstays its welcome. In the realm of bidding games it’s about as simple as it gets–perhaps No Thanks is the simplest, but it is completely abstract, whereas For Sale has the veneer of a theme, no matter how unrealistic and pasted on. It’s no Modern Art, it’s definitely no Neue Heimat (to me, the ne plus ultra of bidding games, worthy of its own column somewhere down the line), but it’s as good an introduction as you will ever get, and essential part of any collection. Why don’t you own it yet?

Comments

No comments yet! Be the first!