Quick: name a boardgame about buying and selling property that’s been around for over half a century, has a simple set of rules, has been released in many versions and languages, and still holds up today as an enjoyable game with a mix of strategy and luck.

If you said Monopoly, you’d be wrong–although Monopoly’s okay when played with the actual auction rules and the quickstart variant where players start with some property and without the stupid but all-too-commonly-used “Free Parking” houserule…but that’s another article entirely.

No, you’d not only be wrong but lazy, because the answer is up top. Acquire has passed the half-century mark and was just re-released under the Avalon Hill imprint of Hasbro. It was designed by the legendary Sid Sackson, who also designed Can’t Stop, I’m the Boss, and dozens if not hundred of other games. Again I make a mental note to devote an entire article to him one day.

In the introduction his book A Gamut of Games, Sackson explains the inspiration for Acquire. As a child he bought a copy of Lotto, an ancestor of Bingo. Even at that tender age he found the lack of strategy underwhelming, and devised his own history-themed solitaire game using the components: a rectangular grid and discs that were placed on the grid as they were drawn.

In the introduction his book A Gamut of Games, Sackson explains the inspiration for Acquire. As a child he bought a copy of Lotto, an ancestor of Bingo. Even at that tender age he found the lack of strategy underwhelming, and devised his own history-themed solitaire game using the components: a rectangular grid and discs that were placed on the grid as they were drawn.

He writes: “A lonely kid uprooted from city after city by a father in search of unemployment during the 1930’s filled many an otherwise empty hour watching empires rise and fall, including the time Finland conquered all of Europe. From the same inspiration of the grouped discs there later came the idea of forming hotel chains, enlarging them, and merging them. This […] became my game of Acquire…” (Gamut of Games, vi)

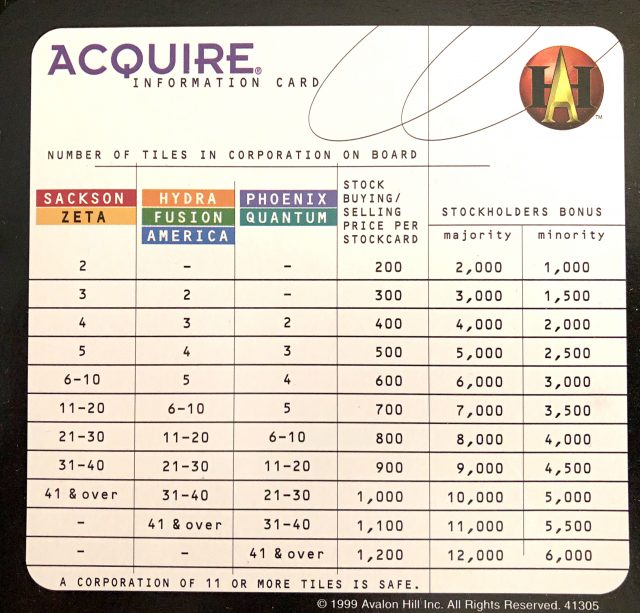

In Acquire you play a tycoon buying and selling shares in corporations (I’ll call them “corps” because I’m lazy.) In different editions of the game those corps have been hotels, generic corporations, hi-tech startups, and so on. The corps are not all created equally: two have cheaper shares and the lowest payouts, two have more expensive shares and the highest payouts, and three are in the middle.

The board is a 12 x 9 grid of individually-labelled squares, from A1 to I12, each of which has a unique corresponding tile, which represents more a unit of value than a physical city block. At the start of the game a few tiles are randomly placed to seed the board.

Players start with a bit of seed money and a hand of six tiles. On your turn you must place a tile. The moment two orthogonally adjacent tiles are placed a corp is created; the player who places the tile gets to decide (usually) which currently-unused corp is born. The value of a corp’s shares as well as its payout at any given time therefore depends on whether it’s the low, medium, or high category as well as its size, in tiles.

After placing a tile you may buy up to three shares of any corp currently represented on the board. But be careful not to run out of money, because you only get more if a corp you currently have shares in merges with another.

The merging rules are the core of the game. The moment someone places a tile that joins two existing corps together into one contiguous blob, the bigger one (in tiles) absorbs the smaller one. The players with the most and second-most number of shares in the disappearing corp get a cold hard cash bonus. Then, anyone with shares in the smaller corps can hold onto them for later (if that corp is revived), or trade in their shares for money or shares in their new corporate overlord, if any are still available. But it’s the first- and second-place bonuses which power the game forward and provide the strategic and tactical focus.

The merging rules are the core of the game. The moment someone places a tile that joins two existing corps together into one contiguous blob, the bigger one (in tiles) absorbs the smaller one. The players with the most and second-most number of shares in the disappearing corp get a cold hard cash bonus. Then, anyone with shares in the smaller corps can hold onto them for later (if that corp is revived), or trade in their shares for money or shares in their new corporate overlord, if any are still available. But it’s the first- and second-place bonuses which power the game forward and provide the strategic and tactical focus.

One ideal situation is to be the majority shareholder in a high-value corp which is absorbed by a larger rival. But there are lots of other successful Acquire strategies. If you have a tile in hand which can merge two companies, you are in a position to make money if you have the wherewithal and time the merge right. But if you start buying shares in a corp out of the blue, observant players will note this and might jump onboard or worse, play a tile that will merge two other companies, wrecking your plans. This is especially true in the mid-game, when there are many merge possibilities.

In the late game, some corps get so big they become immune to merging–they can no longer absorb nor be absorbed, although they can still grow by single tiles. The moment that one corp reaches 41 tiles or (less likely) all seven corps are on the board and no more merges are possible, the game is over. Each corp on the board does one final payout (with bonuses) and the player with the most money wins, just like real life.

Although opening plays can sometimes be formulaic (play a tile; form a corp; buy three shares in that corp), the randomness of the tile draws guarantees that every play of the game will develop differently. Some people like playing Acquire with money and shares hidden. I do not, because it turns the game into an exercise in memory and I’m too old for that. Playing with open shares but hidden money is fine by me.

Sackson tinkered with the mechanics underlying Acquire in a game he originally called Property which he included in his seminal book A Gamut of Games, published in 1969 and still in print, and why don’t you own it yet? Property also used a square grid with players buying property and/or paying rent by playing pairs of cards from hand. After some more development it was published as a standalone game, New York, in German only, 1995. The fact that there has been no new edition since does not necessarily mean that it’s a bad game; the comments on BGG are quite positive, and I’d like to give it a try if anyone out there has a copy.

If you’re sick of Monopoly (and who isn’t) but are looking for a great business-themed game, you could do a lot worse than getting Acquire. It still sits just outside the top 200 on BGG’s all-time list, and there are plenty of copies floating around on BGG and elsewhere–though the 1960’s era editions can set you back quite a pretty penny. Since the rules have basically stayed unchanged since its first release, it doesn’t matter what edition you get from a gameplay perspective. The difference between the editions is in the components and the names of the corps. This is a game that is easy to teach and learn but hard to master–just the way I like it.

“In the late game, some corps get so big they become immune to merging–they can no longer absorb nor be absorbed, although they can still grow by single tiles.”

This might be different in different editions, but I believe these corps can still absorb smaller ones, just can’t be absorbed any more.

But anyway, yes, great game. I like with hidden stocks and don’t even bother to memorize (prevents the analysis-paralysis of counting exactly the effects of every possible move), but one of the many great things is the game works either way.